- SCRUTINY | Moussa Concerto Sounds Strong In Toronto Symphony Orchestra Premiere, Paired With Playful Don Quixote - April 4, 2024

- SCRUTINY | Esprit Orchestra At Koerner Hall: Ligeti 2, Richter No Score - April 1, 2024

- SCRUTINY | Sibelius & New Cello Concerto By Detlev Glanert Offers A Mixed Bag From The TSO - March 28, 2024

Louis Riel. Harry Somers (music) and Mavor Moore (libretto). Canadian Opera Company. At the Four Seasons Centre. Continues through May 13. Go to www.coc.ca.

Overdue by decades, the Canadian Opera Company revival of Louis Riel arrives in some respects at an inopportune time. Emotions are running high on aboriginal affairs, and reason is at a premium. Yet the three-act opera by Harry Somers (music) and Mavor Moore (libretto) proves resilient enough to withstand (or sustain) a good deal of supplemental commentary while reminding us of how hard it is to build a country.

It should be said that this is not quite the Louis Riel you (or your grandparents) saw in 1967. Director Peter Hinton has adopted a more abstract approach than did Leon Major. A statement by a Métis activist is interpolated at the beginning and a squad of mute characters representing the First-Nations perspective supposedly absent from the drama (but in fact pervasive and unmistakable) point accusatory fingers at the audience before positioning themselves portentously around the mostly barren stage.

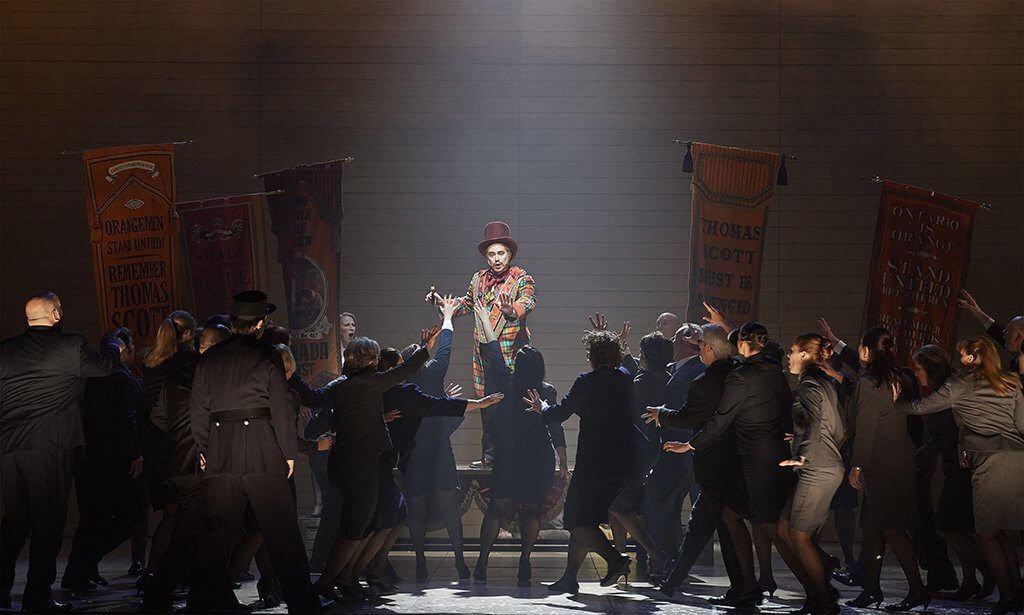

Happily, Hinton is an expert at slow-motion pedestrian ballet, so these observers (who also function as classic supernumeraries) seemed more or less integrated into the drama. And while an on-stage “audience” of establishment types is an international operatic cliché, the business-suited chorus periodically seated at the rear in a jury box could be accepted as a token of the contemporary ramifications of the conflicts that unfold in the story.

That story is about a visionary but troubled leader of the kind that has always made for good opera. Baritone Russell Braun, a great favourite in the Four Seasons Centre, was a three-dimensional Riel whose delusions of grandeur (in an impassioned Act 1 soliloquy he declares himself the new King David) are not out of keeping with the scale of his mission: creating a Manitoba that affords fundamental trading and property rights to its Métis and other inhabitants.

Braun was in good voice on Sunday, which he had to be, since much of Somers’s declamatory writing is solo and/or fortissimo, with neither strophic repetition nor steady orchestral accompaniment to support the sheer act of singing. All of his arias were gripping but his final statement to the court in Regina – in which he confounds the insanity defence with his eloquence — could rightly be called a tour de force.

His was not the only compelling performance. Bass Alain Coulombe summoned vocal and dramatic gravitas as Bishop Taché, the well-meaning emissary between Ottawa and the provisional Métis government (and something of a father confessor to Riel). Baritone James Westman did what he could as Sir John A. Macdonald, who is seldom given anything rewarding to sing.

One flaw of the opera, arguably, is its unduly skeptical portrayal of our first prime minister, although his pragmatism is apparent in Act 1 and he does ingratiate himself to the audience with the best laugh lines in the opera. It did not help Westman that he had to work in a ludicrous plaid suit apparently on loan from Don Cherry.

Thomas Scott, the obstreperous surveyor whom the Métis executed for what they viewed as insubordination, is gruffly played by tenor Michael Colvin. In what amounts to the turning point of the tale, Riel allows the sentence to be carried out despite the pleading of Donald Smith (tenor Aaron Sheppard) and Riel’s mother Julie (mezzo-soprano Allyson McHardy) and sister Sara (soprano Joanna Burt, a Métis artist). Though of two minds, Riel decides that Scott should die for his blasphemy. Alas! The only folly greater than the execution of Scott was the execution of Riel himself.

Or so it seems to me. Canadian history can be messy. All the same, the focus on Riel keeps the drama intact. It is interesting that by finding domestic peace in exile in Montana, the Métis hero also gave Somers the option of softening his tough-to-atonal style. Soprano Simone Osborne, as Riel’s wife Marguerite, made a luminous thing of the Kuyas lullaby at the beginning of Act 3, the Nisga’a origins of which are discussed in the printed program (Marius Barbeau and Sir Ernest MacMillan collected and transcribed the tune).

While Kuyas is not the only oasis of lyricism in Louis Riel, the bulk of the writing is meant to underline the many confrontations, verbal and physical, that lead to the tragic climax of the story. Dissonant as the score is, it is by the same token lucid and economical. There is much percussion, as might be expected, but also starkly beautiful interludes for that most universal of instruments, the flute (as played by the unflappable Douglas Stewart). Whether the need was for something prayerful, menacing, sardonic or violent, Somers found a way of making the music fit the drama. Certainly the final visit by Riel’s mother in his jail cell stands as a remarkable example of how moving and beautiful a free harmonic language can be. Hats off to McHardy here for producing the warmest sounds of the afternoon.

There were other admirable efforts. Jean-Phillipe Fortier-Lazure was sympathetic as the frontier priest who is threatened by intruders and displaced by Riel himself. Another tenor, Andrew Haji, made a brief but ringing contribution as Gabriel Dumont, who convinces Riel to return to his mission.

It would be difficult to credit everyone, not simply because the cast exceeds 25 but because Somers is selective in his use of operatic rhetoric. Often characters express themselves in an intermediate speech-song style that requires punch and clarity but nothing resembling bel-canto curvature. English and French are mixed and Cree and Michif make appearances. There is room also for folk singing by Jani Lauzon, a striking figure who appeared to act as the leader of the lookers-on (and became, quite inappropriately, the clerk reading the charge at Riel’s trial).

The remarkable thing is that despite all these elements (and incongruities) this production of Louis Riel holds its own as music-drama. It did so on Sunday thanks to taut leadership of the COC Orchestra by Johannes Debus and chorus that was both disciplined and flexible as prepared by Sandra Horst.

As for the stage direction, if Hinton tried too hard to add comment where none was needed, this was probably understood to be part of his assignment. Set designer Michael Gianfrancesco also did good work given the preconditions. The bonfire representing Riel’s mystical vision in Act 1 was an inspired touch, and if the Song of the Buffalo Hunt was drained of the raucous energy it had in the original production, there was a vivid (not to say ruthless) treatment of the mob clamouring for revenge.

While some observers have looked warily on this 50-year-old collaboration of two white guys, the perspective is favourable to the cause of human rights and critical of the establishment. Riel comes across as a great if imperfect leader. Works for me.

Correction: April 26, 2017. A previous version incorrectly stated that the production uses a song with the approval of representatives of the Nisga’a. The permission to use this song by the Nisga’a is still in process and has not yet been finalised at the time of this publication.

For more REVIEWS, click HERE.

#LUDWIGVAN

Want more updates on Toronto-centric classical music news and reviews before anyone else finds out? Follow us on Facebook or Twitter for all the latest.

- SCRUTINY | Moussa Concerto Sounds Strong In Toronto Symphony Orchestra Premiere, Paired With Playful Don Quixote - April 4, 2024

- SCRUTINY | Esprit Orchestra At Koerner Hall: Ligeti 2, Richter No Score - April 1, 2024

- SCRUTINY | Sibelius & New Cello Concerto By Detlev Glanert Offers A Mixed Bag From The TSO - March 28, 2024