When I was a young man, I used to pride myself on being able to tell one orchestra from another on recordings. For me, the distinguishing feature was the sound of the oboes. John de Lancie, principal oboist of the Philadelphia Orchestra had a distinctive big sound, as did Harold Gomberg with the NY Philharmonic, Ralph Gomberg (Harold’s brother), with the Boston Symphony and Ray Still with the Chicago Symphony. In Europe the two orchestras making most of the recordings in the 1950s were the Berlin Philharmonic (BPO) and the Vienna Philharmonic (VPO). The Berlin oboes had a distinctive, almost vocal purity — Lothar Koch perhaps best exemplified this sound — while the Vienna oboes were woody and dry. Although these distinguishing oboe features are not nearly as pronounced in most of those orchestras today as they were years ago, the Vienna oboe sound has not changed a bit. The Vienna Philharmonic, known for its respect of tradition, consciously aims to maintain the same sound it always had.

These thoughts came to mind when I learned that the BPO had mounted a special exhibition, “The Oboists of the Berliner Philharmoniker”, honouring the oboists who have played in the orchestra over the years, in the foyer of the Philharmonie hall where it performs. One of the most distinguished oboists in the orchestra’s history was Helmut Schlövogt, who played in the BPO from 1941 to 1974. The exhibition includes a collection of mouthpieces from Schlövogt’s estate and the tools oboists need to makes their reeds. For more on the exhibition visit the orchestra’s website.

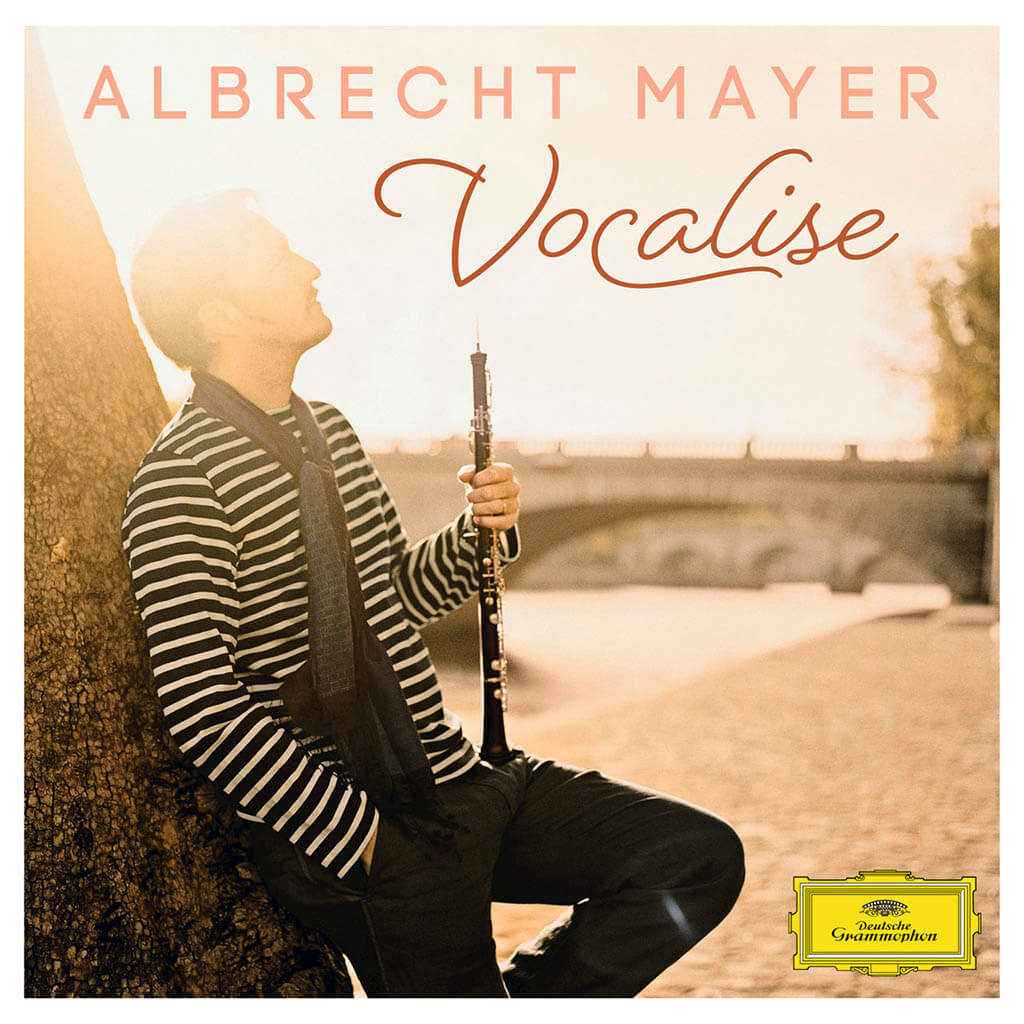

For many years the BPO has had not one, but two principals, for almost every section of the orchestra. At the present time, the two oboe principals are Albrecht Mayer and Jonathan Kelly. Mayer has been featured on many recent Deutsche Grammophon recordings and the present CD is a compilation of excerpts from some of them with repertoire ranging from Bach (1685-1750) to Julius Weismann (1879-1950). The music is well-chosen to show off Mayer’s artistry in a variety of instrumental and vocal settings. Mayer’s switching from oboe to oboe d-amore to cor anglais in different pieces also helps to hold the listener’s interest. Unfortunately, the CD booklet is not entirely accurate as to which instrument is used in which piece. For the record, Albrecht Mayer plays an oboe built by Gebrüder Mönnig, Markneukirchen and uses BAI reeds.

Anyone listening to this recording for more than a few minutes will be struck by the singing, flutelike tone that is characteristic of Mayer’s playing and which has been an attribute of oboe players in the BPO for a very long time. Mayer, who studied with the great French oboist, Marcel Bourque, emphasizes the French influence on his playing and believes that the preferred oboe sound today is more beautiful than it was in the past: “If you listen to old oboe recordings, you’ll find that they sounded very acidic, very thin, a little aggressive.”

For me, one of the highlights on this disc is Mayer’s own arrangement of Mozart’s concert aria “Ma che vi fece,” K. 368. At his most virtuosic here, Mayer is given a stylish and precise accompaniment by Abbado and the Mahler Chamber Orchestra. Another winner is Pavane pour une infant défunte, in an exquisite arrangement for oboe and chamber orchestra by Chris Hazell, which is almost as good as the original by Ravel. Similarly, the Pavane Op. 50 by Fauré with Mayer playing oboe d’amore, and Debussy’s Clair de lune — also Hazell arrangements — are lovely. The “Children’s Prayer” from Humperdinck’s Hansel and Gretel, with the King’s Singers taking the vocal lines and Mayer providing an oboe obbligato in an arrangement by Joachim Schmeisser, is heartbreakingly beautiful.

Finally, there are some original oboe pieces, among them Schumann’s Romance Op. 94 No. 2 which Mayer plays seamlessly, and with a freedom of expression that seems to me just about ideal.

Unfortunately, there is no contemporary music in this compilation. Surely some appropriate music by living composers could have been found. That said this is — on the whole — a well-chosen selection of compositions just about flawlessly executed by one of the foremost oboists of our time.

For more RECORD KEEPING, see HERE.

#LUDWIGVAN

- SCRUTINY | TSO Lets Berlioz Do The Talking In Season Opener - September 21, 2018

- RECORD KEEPING | Even Yannick Nézet-Séguin Can’t Make Us Love Mozart’s La Clemenza di Tito - September 6, 2018

- RECORD KEEPING | Giovanna d’Arco With Anna Netrebko Explains Why The Best Operas Survive - August 30, 2018