Music has been a major theme in nearly all the novels of Haruki Murakami – you can even find playlists on the Internet based on the listening habits of his characters – and this is a reflection of the obsessive passion the Japanese writer has for music, especially jazz and classical. Murakami spent a decade running a jazz club in Tokyo when he was young, and he estimates now that he owns 10, 000 records.

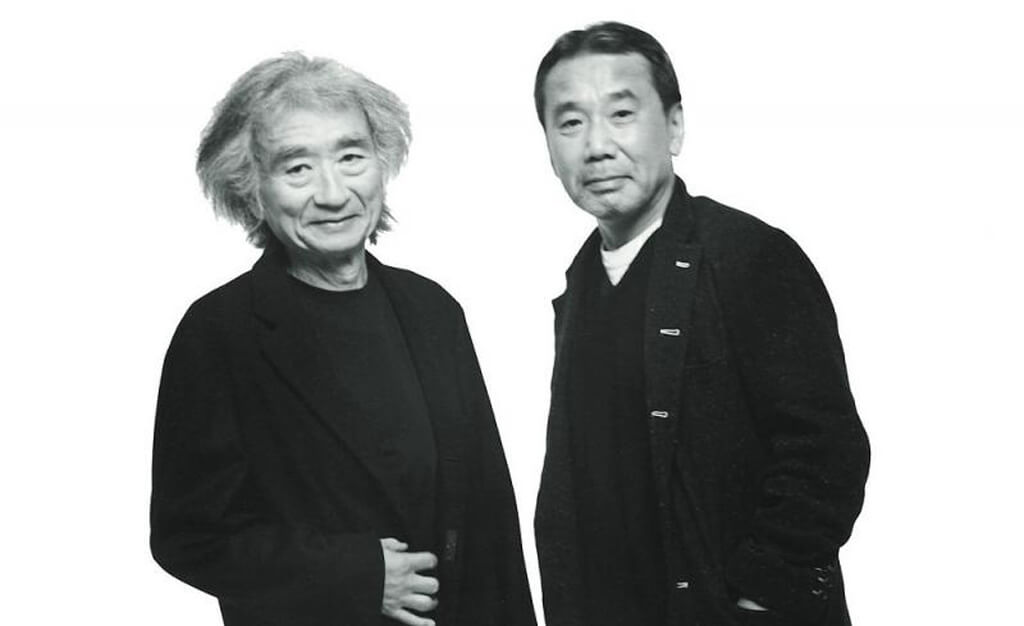

In Absolutely on Music (out November 15, 2016, on Knopf), readers are given a new window into Murakami’s passion for music, as well as that of his friend, the great conductor Seiji Ozawa. A transcription of conversations about music the two friends conducted over a two-year period, the book is a rare opportunity to encounter Ozawa in a personal context, as he reflects on his long career, goaded on by the literary and artistic sensibilities of Murakami. Ozawa tells stories, Murakami asks questions, and together they spend hours and hours listening to music and analyzing it.

These conversations are especially valuable for what they reveal about the day-to-day life of a high-profile music director, and for Ozawa’s observations about how orchestras have evolved in the last fifty years, both artistically and administratively.

Ozawa’s storytelling also makes for enjoyable reading. We hear about his failed attempt to steal a baton from Eugene Ormandy’s collection, and we get an insider’s perspective of the legendary 1962 New York Philharmonic concert where Leonard Bernstein (or Lenny, as Ozawa knows him) publically disassociated himself from the Glenn Gould interpretation of the Brahms Piano Concert no. 1 that was being presented. Ozawa was Bernstein’s assistant conductor at the time, and Bernstein had considered passing the baton to him that evening — a job Ozawa seems relieved to have been spared.

Murakami’s and Ozawa’s respective geniuses complement each other nicely throughout these conversations. Murakami approaches music poetically, metaphorically; he describes a passage from Brahms as an invitation into a dark German forest, and likens the conducting work Ozawa does to slowly tightening the screws on a vast, complex machine. He freely admits his lack of technical knowledge. Ozawa, on the other hand, comes across as compulsive in his attention to details; he spends hours pouring over scores, not looking for meaning or narrative but focusing only on the music as pure music. Taken together, the writer’s and the conductor’s approaches form a whole.

Ozawa has a special relationship with the Toronto Symphony Orchestra. He was the orchestra’s music director from 1965 to 1969, and Toronto readers will enjoy the casual references Ozawa makes to this period throughout the book, even if he is occasionally a little disparaging. When asked by Murakami about the TSO’s level of playing in the 60s, Ozawa flatly responds, “It was not very good, to tell you the truth.” And he wasn’t impressed with the TSO’s venue at the time either, Massey Hall: “It was famous for its bad sound,” Ozawa tells Murakami. “People used to call it ‘Messy Hall.’”

But Ozawa’s time in Toronto, which was the first chance he had to lead a major orchestra, proved to be formative. The TSO’s youth at the time complemented Ozawa’s own, and despite his criticisms, Ozawa acknowledges the Toronto Symphony players had incredible enthusiasm. Ozawa’s influence is still felt at the TSO today — the musicians he hired in the 60s are still there, he notes.

Occasionally, the conversations devolve into unnecessary name-dropping, with Ozawa being especially of guilty of pursuing lines of thought that don’t lead anywhere. But these are real, live conversations, recorded in offices and living rooms, and the spontaneity and candidness they possess are worth the occasional uninteresting passage. And since the book is not organized as a narrative, it lends itself easily to reading in bits and pieces, so when Murakami and Ozawa pursue a topic the reader isn’t interested in, there is no consequence in skipping it.

A sense of comradery and friendship pervades Absolutely On Music. Murakami and Ozawa are both clearly thrilled to have the chance to discuss music together at such length and with such leisure. But the opportunity was bittersweet for Ozawa; it was made possible by a diagnosis of esophageal cancer that stopped him from travelling and conducting, freeing up the time for these conversations. He reflects near the end of the book that he’d been so busy making music up until his surgery that he never had time to think about the past. Absolutely On Music captures the “nostalgic surge” that welled up in Ozawa as he recovered. It appears to have had a recuperative effect on the conductor, and we might all take heed not to wait for illness to pause and take stock of our own histories.

#LUDWIGVAN

Want more updates on Toronto-centric classical music news and review before anyone else finds out? Follow us on Facebook or Twitter for all the latest.

- FEATURE | Beyond The Concert Hall: Toronto’s Church Music Scene - November 22, 2018

- FEATURE | Where To Buy Classical Vinyl In Toronto - December 9, 2016

- SCRUTINY | A Cult Novelist Makes Great Conversation With Former TSO Conductor Seiji Ozawa - October 31, 2016