The Winter’s Tale: A Ballet in a Prologue and Three Acts. Based on Shakespeare’s play The Winter’s Tale, with choreography by Christopher Wheeldon. Until Nov. 22 at the Four Seasons Centre, 145 Queen St. W. For tickets visit nationalballet.ca or call 416-345-9595.

Much has been written recently about the transformation of Christopher Wheeldon’s choreographic style in the wake of his tremendously successful three-act adaptation of Shakespeare’s The Winter’s Tale. After taking Covent Garden by storm in last year’s Royal Ballet season, the hit story-ballet arrived at the National Ballet of Canada, where the work is being met with similar plaudits from critics and fans alike. I rarely see a ballet audience simultaneously leap to its feet so quickly when the entire ensemble cast appears on stage for bows at the end of a performance, as I witnessed Sunday afternoon.

But such was the scene this weekend of what proved to be a remarkable North American premiere at the Four Seasons Centre, a veritable triumph for Mr. Wheeldon’s new work and a vindication of sorts for what many believe to be a departure of style from his more populist productions of the past, such as his previous National Ballet co-production Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland or Carousel (A Dance), to name only two examples.

Still I have doubts that this is truly a stylistic departure of any kind. It seemed to me that what we saw this past weekend was another sincerely epic Wheeldon production with all his most common elements intact: larger-than-life corps movement consisting of central production numbers, a dance language mindful of audience accessibility first and foremost, soloists with whom one can readily identify, and definitively crystal-clear moments when a good story-ballet carries an immediacy of communication connecting on-stage action to its audience at all times.

Mr. Wheeldon knows how to please. But he also knows how to tackle a difficult story and tell it well with some truly inspired dance, regardless of whether he is dealing with intractable abstractions (of which there are plenty in the original Shakespeare play), or with a story arc’s emotionally redemptive directness of utterance. Ultimately, The Winter’s Tale presents genre-bending problems that quite frankly, fade before our eyes, and we don’t care a whit about the play’s dramatic problems simply because Wheeldon has adroitly taken care of all that in his ballet. He knows how to make a tale of redemption sell itself, taking us by the hand, and guiding us as we sail through stormy seas from bleakest tragedy to restorative comedy.

The central leitmotiv of the ballet, after all the non-essentials are stripped down, is the inexplicable grip of madness that descends on a Sicilian king (Leontes, danced by Evan McKie) who believes he is cuckolded by his best friend (Polixenes, danced by Brendan Saye). With Leontes, it takes the form of a jealousy trope, which in Joby Talbot’s score, returns with an eastern exotic flute flan like a willowy-spirited worm invading one limb at a time.

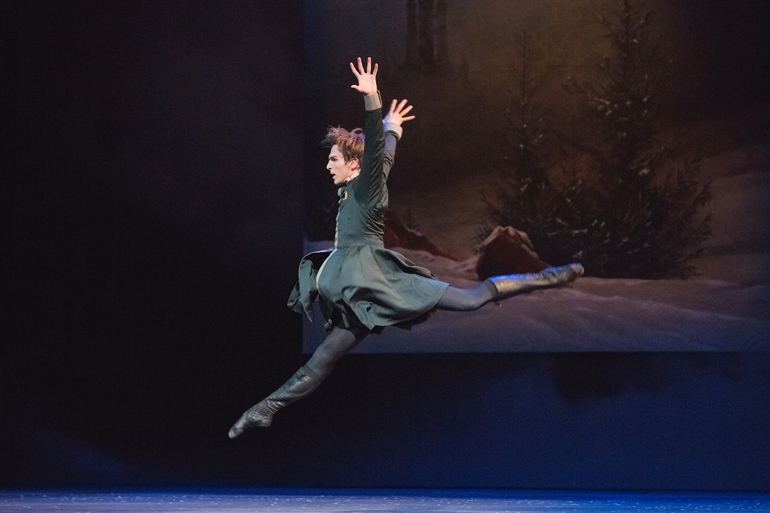

Sunday afternoon’s Leontes (the work has three casts) was played subtly and at all times commandingly well by Mr. McKie, who evoked the green-eyed monster as a crawling virus that infects one muscle and then another, creeping from chilling moment to moment until it totally possessed him. In fact, I enjoyed Mr. McKie’s performance thoroughly all afternoon. Even though my flight plans were changed in the last minute and I could not catch opening night as well, Mr. McKie made it all feel like an opening anyway, his acting and dancing being so compelling as to convince me anew of the metaphorical earnestness central to the ballet’s wintry theme. The audience clearly loved him.

Each time the jealousy motive returned, Mr. McKie took it to a new level of malady, portraying its progressive infection with each modified turn and slow pirouetted leg extension, followed by a mildly contorted upper body hunch. Mr. McKie descended upon his wife Hermione like a predatory vulture and made us realize that Winter’s Tale is about his own wintry descent into a horrifying illness he cannot stop, one which costs him the lives of family and friends, and the near loss of his daughter Perdita (Rui Huang), who returns to be found later in classic Shakespearean style.

In fact, Mr. McKie was the perfect martinet, a man who often made the spinal straightness of his sculpted vertical stature seem demon-possessed in marionettish stiltings, the strings of his emotions pulled by an unseen force.

Jurgita Dronina’s Hermione was modest, demure, and vulnerable, setting up her betrayal by the middle of Act 1 perfectly. And when she comes to rest in a fourth position croisé when she stands accused by her husband, the horrid moment of the plot’s injustice, conveyed ably well by a radiant Ms. Dronina, perfectly demonstrated how any of us might feel when we are betrayed deeply by someone we love and respect,

The denouement of Svetlana Lunkina’s Paulina, pounding her fists upon Leontes, literally forcing him into submission upon the ground in grim realIzation of his inexorable guilt at destroying his entire family, was followed by the most beautiful moment in the entire first act – a tenderest pas de deux of recognition in which Paulina realizes she must remain with her monarch to help him traverse his long dark winter’s journey ahead. Ms. Lunkina’s grace formed an able counterpoint to the previous Trial scene with its psychologically disturbing pas de deux of powerful destructive force danced well by Ms. Dronina and Mr. McKie, cast in sharp but never overdone dramatics. Mr. McKie was again perfect and made the internal drama count for more than the external theatrics while Ms. Dronina danced her innocence in perfect traditional ballet combined with more subtler moments of stylistically modern angst, a typical Wheeldon signature.

Joby Talbot’s score was perfect to match, especially the lovely piano solo when Paulina enshrouded Leontes on stage right during the close of Act I. The bear scene was equally fine, one of many beautiful Basil Twist silk designs, perfectly lit by Natasha Katz’s lighting and often glorious projection. However I could have done with more dancing at that point from Antigonus for such a famous line of Shakespearean staging, especially given that the bear is the perfect symbol for winter consumption and total digestion – the worst of fates for the entire cast, victimized by Leontes’s wanton negligence of his demented faithlessness toward his wife and all others. And the orchestra was splendid through the first act, handling the British film/television-inspired score at every point with brightness and characteristic precision of phrasing.

The mood changed in Act II from the dour Sicilian court plunged in mourning, to Bohemia setting the stage for the imminent wedding of Leontes’ long-lost daughter Perdita and Pollixenes’ son Florizel. The act centres largely on some lovely duet work for Ms. Huang and Skylar Campbell (Florizel).

We were also treated to a fairly typical Wheeldon extravaganza of straight-up dancing, shapely choreography of broad, stage-filled arcs at times over-stuffed with gratuitous joy. But what can one expect from a wedding atmosphere? Bob Crowley’s stage design outdoes itself with what looks like a glorious Bodhi tree, under which a brilliant corps frolics, filled with Bohemian exuberance.

But, of course, another misunderstanding ensues, and it is now Pollixenes who ruins his family by chasing his son away, refusing his request to marry someone who appears to be a poor shepherd girl. The shoe is on the other foot now, and the couple flee to Sicily, where they are embraced by a repentant Leontes, in a beautifully presented recognition scene where all is forgiven.

But, of course, there is much more to the tale and its famously rapturous ending, where it is discovered that Hermione herself is not lost to Leontes as he had thought. Hermione ends her own frozen wintry immobility when she transforms from statue back into a woman again via a dramatic descent from her pedestal before her shocked husband’s eyes. She can only do so by faithfulness, complete with choreographic gestures in upturned arms to depict spousal loyalty through time – she even makes her husband make the same gestures, as he breaks down in final realization. I wished I could have watched their gorgeous pas de deux again and again.

A true gem of Shakespeare’s classic recognition scenes, The Winter’s Tale contains some of the best elements of the bard’s plays, leaving little doubt that anagnorisis (recognition) comes in no better form than when we seek to understand our own blindness, here beautifully depicted in Ms. Katz’s darkened, psychological grey hues that gradually transformed into diffuse soft white lighting. And best of all, the ballet provided a complete account of Shakespeare’s descriptive wintry emotional despair, available for us all to experience via Wheeldon’s expressive choreography and Mr. McKie’s consummate acting.

The final scenes were stunning, particularly throughout the compelling narrative crescendo when the contrasting darkness is lifted via gradual lighting transitions during the eloquent pas de deux, brilliantly captured by Ms.Dronina’s Hermione in all her statued beauty, melting into unfrozen dissolutions, first in her face (brilliant acting), next in her shoulders, and finally, when she moves her whole body, as though she has been thawed from her husband’s prison of interminable neurosis and inexplicable abuse.

The ballet’s miraculous ending solves what the stage may struggle to do: reconcile the wintry fusion-genre of Romantic tragedy and restorative pastoral comedy, making Mr. Wheeldon’s triumph in his new career direction a story for the ages. We will surely be performing his Winter’s Tale for decades to come.

#LUDWIGVAN

Want more updates on Toronto-centric classical music news and review before anyone else finds out? Get our exclusive newsletter here and follow us on Facebook or Twitter for all the latest.

- SCRUTINY | Opera Atelier’s Film Of Handel’s ‘The Resurrection’ A Stylish And Dramatic Triumph - May 28, 2021

- HOT TAKE | James Ehnes And Stewart Goodyear Set The Virtual Standard For Beethoven 250 - December 15, 2020

- SCRUTINY | Against the Grain’s ‘Messiah/Complex’ Finds A Radical Strength - December 14, 2020