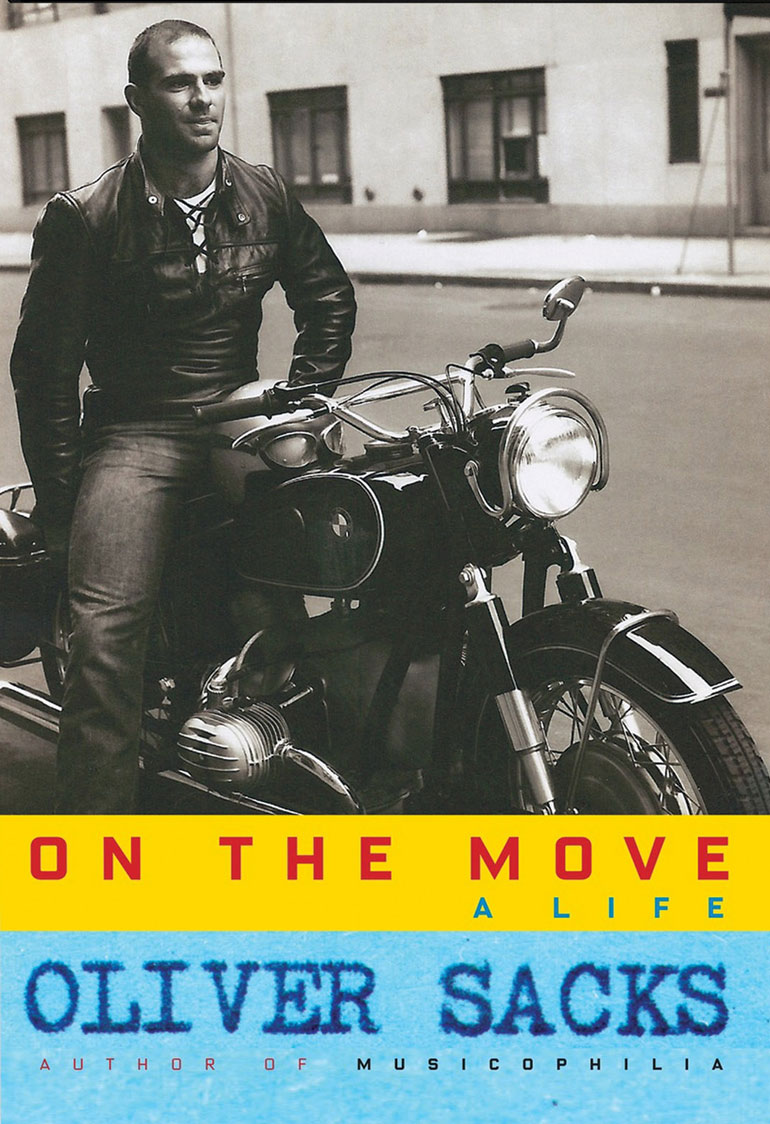

On the Move: A Life By Oliver Sacks. 397 pages. Hardcover $32. 2015. (Knopf)

At the recently concluded XVth International Tchaikovsky Competition, the candidates were each asked which guests they would like to invite to their dream dinner party. Most of the answers to a question I find particularly pleasant to contemplate were unimaginative and mundane, though the Second Prize winner and U.S. candidate, George Li, nominated all the world leaders “to at least have a moment of peace throughout the world” which showed some vision. One person who I’m sure these world-class pianists would be enriched by entertaining is Oliver Sacks, one of the leading intellectuals of our day, whose body of neurological writings often touches on music and whose recently released memoir, On the Move, reveals a personal love of music.

Music has a forceful presence in Sack’s life, in good times and bad. After delivering the manuscript of his first book, Migraine, to Faber and Faber, he was so elated that he “wanted to shout, “Hallelujah!” but I was too shy. Instead, I went to concerts every night — Mozart operas and Fisher-Dieskau singing Schubert —feeling exuberant and alive.”

There’s a surprising Mozart/Ontario connection that will please Lake Huron enthusiasts. While working on the book that was eventually published as A Leg to Stand On, Sacks retreated to Manitoulin Island, with two pieces of music — the Mozart Mass in C Minor and the Requiem. Not only did he listen to these pieces while writing the book, they were central to the subject of his book, which was the near fatal accident he suffered when he broke his leg while hiking alone on a mountain in Norway. For eight hours, as he dragged himself down the mountain using his arms, these two pieces of music played in his head. Later, when it was time for him to try to walk again, he found that “moving the leg felt like manipulating a robot limb…nothing like normal, fluent walking. …suddenly, I “heard,” with hallucinatory force, a gorgeous, rhythmic passage from Mendelssohn’s Violin Concerto. ,..I found myself suddenly able to walk, to regain…the “kinetic melody” of walking. When the inner music stopped after a few seconds, I stopped too; I needed the Mendelssohn to keep going.”

Surely this is one of the most powerful proofs that music is much more than a profound enrichment of life, but an essential tool for survival. The physiological and emotional resilience Sacks had to muster was available to him because he had already listened to the great classical masterpieces countless times, and installed them in his internal reserve of resources. Even in today’s world, with the endless availability and infinite inventory of music available to us in cyberspace, we still need to devote the time and concentration to actually listen to music in such a way that it becomes part of us. Ear buds and iPods and Wi-Fi aren’t always there for us in a crisis but our internalized melodies can be.

Music alone would not have gotten Sacks through his wildly risky and self-destructive young adulthood and early middle age, which he frankly describes. Accident-filled motorcycle rides, amphetamine abuse, lifting extreme weights (up to 1000 pounds) without anyone to spot him, and risky sexual practices were a regular part of the life of the man who eventually stabilized enough to become an effective clinician and hyper-prolific writer. It is a surprise to learn of Sack’s dissolute beginnings given his dignified and accomplished public persona, as well as encouraging to see how he was able to change the course of his life with determined interventions. Sacks identifies five factors that enabled him to survive to a ripe age: psychoanalysis (for 49 years, even longer than Woody Allan), clinical work, writing, good friends and “above all luck”. How refreshing and candid that he doesn’t default to the standard shibboleths, family or love.

Sacks acquired his lifelong musical nourishment the best way, in his childhood home. His father played an 1895 Bechstein piano well into his 80s and grew up attending concerts at Bechstein Hall before it was renamed Wigmore Hall during World War One. He began playing piano as a child, and after he had moved to California as a young physician, he installed a piano in his home. On occasion, this enabled him to play music with a patient. Most inspiringly, he resumed playing piano and taking lessons, at age 75 when he felt he should be a living exemplar of his contention that elderly adults can continue to learn. His interest in the neurology of music has run through his professional life from his observations on music’s effect on Post-encephalitic patients and their response to music therapy through his 2007 volume: Musicophilia: Tales of Music and the Brain. Though this book is entirely devoted to music, it conveys less of Sack’s personal appreciation of it, focusing on peculiar musical anomalies that leave the sense that music can be experienced as a disease or affliction rather than an uplifting benefit.

Sacks has even been the inspiration for the creation of new music. One of this most famous ‘clinical tales’ as he calls his case studies, which became the title of he breakout bestseller: The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat, is about a musician, and culminates with Sacks prescribing music as the only treatment for this man’s visual agnosia. In 1986, the composer Michael Nyman presented him with the score of a chamber opera based on the case, which was eventually premiered in New York City. Later, a ballet based on the book Awakenings appeared with music by Tobias Picker.

If any of the Tchaikovsky candidates really could host their dream dinner party, they would have to invite Dr. Sacks very soon. He was diagnosed with ocular melanoma in 2005, and earlier this year he learned that it had metastasized to his liver, numbering his days. This memoir was completed before learning of the terminal diagnosis, so this is not addressed in the book, but his profound reflections on his imminent mortality in the New York Times makes a fine encore On the Move. Certainly in my own dinner party fantasy, I would not only make Sacks the guest of honour, I would welcome him to bring along the many eminent friends and colleagues he writes about, including Jerome Bruner, Alexander Luria, Stephen Jay Gould, Francis Crick, Harold Pinter, Jonathan Miller and Robin Williams. This would be an intellectual feast indeed.

#LUDWIGVAN

Want more updates on Toronto-centric classical music news and review before anyone else finds out? Get our exclusive newsletter here and follow us on Facebook for all the latest.