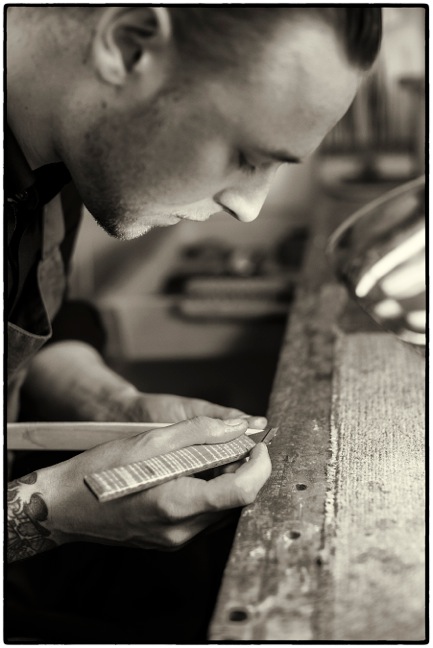

Leyland Hiphner (Lee) wasn’t happy, and that changed everything. The 6’4” B.C. native sits at his workbench doing a general set up of a violin at Geo. Heinl & Co. Ltd. on Church Street in Toronto. Hiphner, 26, is the newest luthier on staff, hired in July, 2013 and seems, frankly, still surprised at his new gig.

Until a few years ago, Hiphner was employed making high-end cabinetry in B.C. but something was bugging him. Hiphner leans back from the violin and in the process, reveals part of what he describes as a rather extensive tattoo peeking out from under the right sleeve cuff of his shirt. The design is all about his grandfather, a mechanic on an aircraft carrier in the Canadian Navy. “It all means something,” Hiphner says, and this is the big clue to how our Hiphner ticks: this need for meaning is what brings him to Toronto.

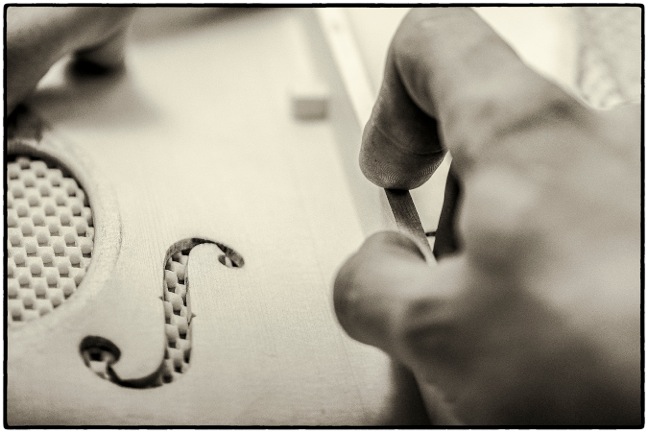

The violin Hiphner is working on was brought in to sell at Heinl’s. “This needs some work if we’re going to represent it in the shop,” he says. Heinl’s is world-class. Seriously. That is a fact and Hiphner knows it. He finishes reshaping the pegs with the Wirbelschnider (looks like a pencil sharpener but the name sounds like beer). He drapes the instrument in a protective bib and begins planing the ebony fingerboard.

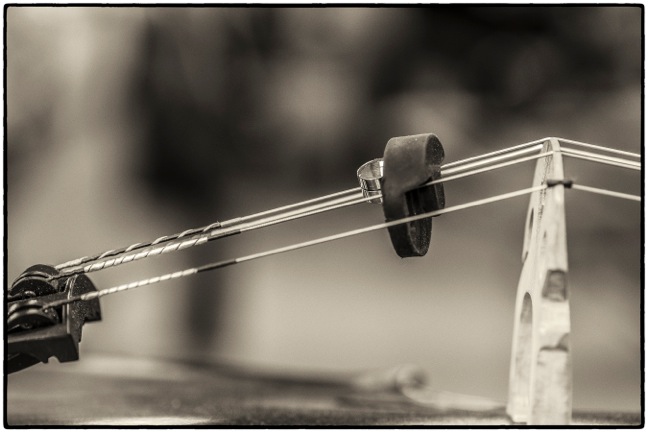

He is surrounded by veteran craftsman, tools and shelves full of the potions needed to either bring an instrument up to snuff, or create a new one. Behind him is a double-burner hot plate under two Game-of-Thrones-ish crucibles simmering special glue. There are violins, cellos and basses everywhere. In one corner, there is a workbench with nothing but bows and perfect swatches of horse hair, likely from perfect horses. There are cellos and a bass laid out on special tables undergoing various forms of detailed work.

- PROFILE | The Tattooed Luthier: New Life in Young Hands - April 19, 2015

There is an odd sense, if you anthropomorphize anything at all, that these instruments are glad to be here. Like they’re getting therapy (“Troy, I never wanted to be a bass. As a sapling, I was kind ‘a keen on the viola. It’s okay. Relax. Tell me about your forest.”).

Hiphner does woodworking all through high school. He graduates with a joinery degree from the British Columbia Institute of Technology, then works in a shop, making high-end cabinetry. Initially, he thinks that this is where he is meant to be. Life is good. The pieces are unique and expensive. He likes the work, but slowly, a relentless, deep realization takes hold like a wolf note that won’t go away: “At the end of the day, you deliver the coffee table. They put their coffee on it and it’s level and it doesn’t spill and they say, ‘Thank you very much,’ and ‘here’s your cheque’ and you leave.”

Hiphner looks up from the fingerboard. “You’re putting your heart and soul into every aspect.” He shakes his head. “They just didn’t appreciate it.” He needs reciprocation. He needs the soul connection that goes with creating something artistically important; as heartfelt for the buyer as it is for the maker. Hiphner’s epiphany comes shortly after and sounds like something from a movie. He and his step-dad start playing cello together. The next thing Hiphner knows, he is interviewing for the Chicago School of Violin Making and another school in Boston. There is a year’s wait for both, so, as the movie goes, he returns home, gets a promotion at work and signs a year’s lease on a new apartment. Phone rings and a-space-is-open-in-Chicago-and-does-he-want-it-and-they-need-to-know-in-24-hours. Hiphner goes crazy. “ I jumped ship, broke my lease, gave away all of my stuff. I went to Chicago with two bags, and it was minus 30!” Three years later he graduates, and then applies to Heinl’s “on a hope.” And here he is.

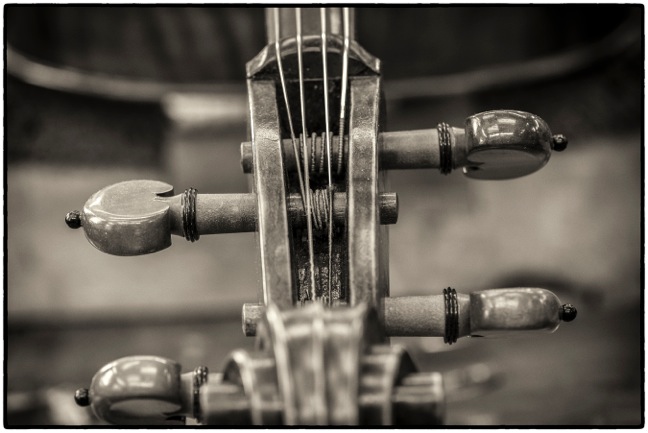

“I love woodworking. I love being able to work with my hands. The biggest thing is that I want to put myself into whatever I do to the full extent, and to have someone else reciprocate it, someone who’s really excited and gung-ho, that’s what gives me a kick.” The idea of making an instrument, something so special with a specific sound that someone is looking for, keen on, is Hiphner’s dovetail (see what I did there?). So, yes, he’s at Heinl’s with a diploma, but there is much learning to do. The craftsmen at Heinl’s use a different method of making than what the Chicago School teaches. Hiphner explains that, in regards to creating the arch on the top and the back which houses the sound cavity, the Chicago School’s students learn to create this almost sacred shape from the outside in. Heinl’s uses the Italian Catenary Method, which involves working sequentially from the inside out. Hiphner is illustrating the method in detail when Ric Heinl, President of the company, hands him a violin. Heinl has a knowing smile on his face and stands back while Hiphner looks inside at the label: “Strad, 1719.”

He then examines the instrument and explains that because of the way the arching is pulled off to the left on the back from the soundpost pressure over time, the label is “incorrect.” He goes on to explain the three Stradivarius periods and how common it is to find copies. Hiphner doesn’t hesitate: he knows his stuff. “Yeah, it’s a copy.”

Hiphner sells the first violin he makes at Heinl’s to Atis Bankas, a prominent violinist with a list of achievements, local and world-wide, that will make your head spin. “It kind of blew my mind,” Hiphner says. He describes how Bankas is visiting the shop and Hiphner asks him to play the finished violin. Bankas borrows it and then, a few days later, returns to the shop. “I’ll take it,” he says. Hiphner smiles. Bankas, talking on the phone from Niagara-on-the-Lake, where he is the founder and Artistic director of Music Niagara, among every thing else, is delighted with the violin. “It made a nice sound,” he says.

Hiphner’s bench is right next to an impressive wall of CDs and the sound system for the room. He likes most music styles and comments that in regards to classical music, he’s “not an expert by any means,” but he’s learning what he likes. Bach and Tchaikovsky are great but he says that the big draw for him is the modern composers. Hiphner likes the pieces written over the last 80 years and mentions John Adams and John Corigliano. “’Totally different styles. Really exciting.” His ideas about where classical music is going do not involve any of the tired old arguments about it dying. “Not at all.” He thinks the repertoire might change a little bit. “It depends on who’s invested in it and with the baby-boomers getting older, it’s hard to say definitively.”

Hiphner has more tattoos planned. Hard to find the time between work and making on his own, but he’ll get to it. Life is good for our Hiphner. “This is going to be really amazing,” he says. Now he’s happy.

#LUDWIGVAN

Want more updates on Toronto-centric classical music news and review before anyone else finds out? Get our exclusive newsletter here and follow us on Twitter for all the latest.