After arguing with the barista about the existence of a café allongé, or long black variant, (Yes that’s an Americano.” No, no it’s not. Yes, yes, it is), I gave up, and told him how to make it myself.

Over my shoulder, composer Andrew Ager walked past with a nonchalant sense of someone who had spent the last evening drinking calvados with a blonde starlet on a beachfront brasserie.

After introducing myself, we strolled over to the café patio, and installed ourselves at an empty corner table overlooking Toronto’s High Park. Before saying a word, we sipped our coffees and squinted at each other. Adjusting his sunglasses, Ager confessed mornings were a bit difficult.

He slouched down into his seat, and spoke facing the street, commenting frequently on the passers-by. I had the distinct feeling that like many creatives, his gaze fixated on the things most of us overlook.

As a composer, Ager has always been a bit of an enigma. He is known as being fiercely independent, and habitually at odds with formal music traditions.

After studying for his Doctorate at the University of Toronto, with Lothar Klein and Derek Holman in 1995-96 (a move he opted as a way to help make ends meet as a teaching assistant), he found himself a poor fit against what he described as the “Polybureau.”

“It was just like Soviet era politics, no dissent; and if you do dissent, then you are ideologically an enemy of the state.”

It all climaxed with his being thrown out of composer John Beckwith’s house after a violent argument.

“…I said, you know what, forget all that, and I just quit.”

Ager turned to freelance composing, and over the years has been in fairly high demand. He also took a seemingly temporary gig as a freelance pianist and church organist, a role that he has been doing on-and-off with Toronto’s St. James Cathedral. He described himself as a “recluse living downtown”, spending his time “writing and doing what I need to do on the job.”

He doesn’t much like the city, preferring rural life in Quebec. He moved there in October of 2010, seeking a space to compose fulltime.

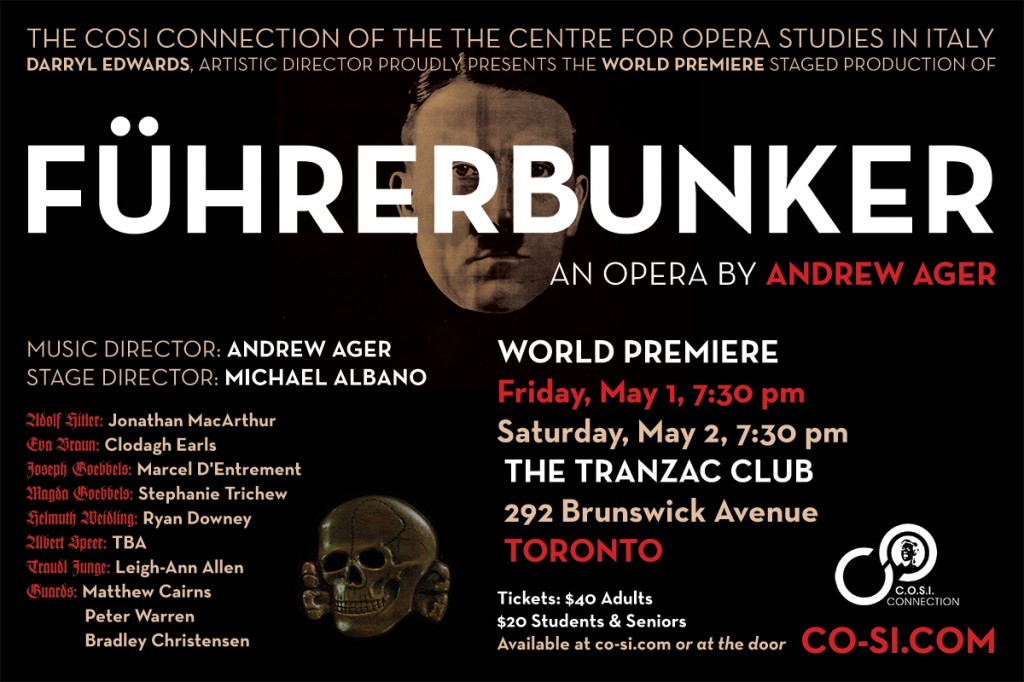

Besides composing for the likes of the Penderecki Quartet, the Elmer Iseler Singers, The Talisker Players, and Sinfonia Toronto, Ager has had an affinity for opera. Past projects include chamber operas: The Wings of the Dove and Casanova, and his most successful to date, Frankenstein, premiered with TrypTych Concert and Opera in 2010, featuring Lenard Whiting, Dawn Baily, Steven King, Michael Taylor among others.

Over the past while, Ager has had his eye on a new obsession, which he described as “slightly problematic”.

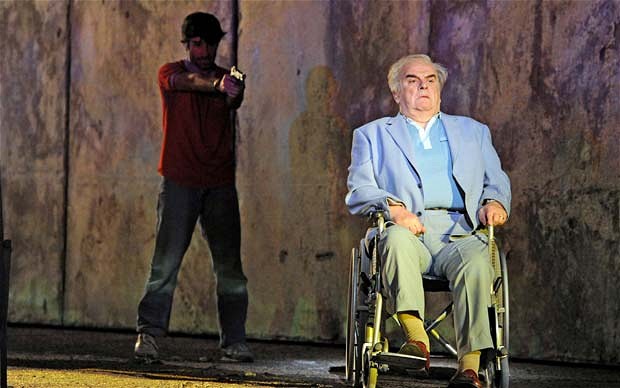

Führerbunker (German for: “Leader’s bunker”) is the name of Ager’s new chamber opera, based on the surreal experience of those stationed with Adolf Hitler in a fabled air-raid shelter located near the Reich Chancellery in Berlin, Germany. It takes place during the dictator’s last 10 days of the Second World War, just before the Russians occupied Berlin in 1945.

Ager seemed noticeably apprehensive speaking about it. “It deals with a topic that I think is actually truly controversial…” He was careful to add that doesn’t mean he choose it for that reason. Ager has had festering and personal interest in pre and post WWII Germany, and its relation to his perception growing up alongside German immigrants in Canada.

“When I was a kid growing up, everyone’s dad was a veteran of WWII. We were surrounded by WWII references, many of which were anti-German. I couldn’t make the distinction between Germans and Nazis. Every reference was Hogan’s Heroes or caricatures of Nazism. We had German neighbours across the street – five gorgeous daughters with whom I used to play and I just couldn’t make this dichotomy.”

Like many baby-boomers, Ager’s grandfather was a first-hand reminder of the war to end all wars. His grandfather fought in WWI at Vimy Ridge, and by the end of WWII, worked as a guard in a POW camp for German prisoners in Bowmanville, Ontario. “He took all the memorabilia he could back home. We had a luger and Nazi armbands in the house, along with his other stuff like his whiskey flask. These were tangible connections to world history.”

To help make sense of this dichotomy, he became interested contemporary dramatic and historical accounts of Nazi Germany.

Ager mentioned the 2004 German war film, Der Untergang (Downfall), which he saw just a few years ago. It was a controversial film, and the first serious take on the death of the Third Reich that portrayed the people in the bunker as “believable human beings who were obviously horrendous war criminals, but weren’t like Hollywood cardboard Nazis with a monocle and a dumb accent.”

The film was heavily criticised for being a sympathetic portrayal of Nazi characters. Some advocated that it presented an uncritical account toward the barbarism of its historical portrayal.

“The actual events that took place could not have been dreamt up by the best of opera writers, because they were so surrealistic and strange. The atmosphere was unreal, bizarre and pressured…”.

After starting work on Führerbunker, Ager was warned by colleagues to tread carefully. “They said, ‘you can’t do that – you can’t write an opera about Aldolf Hitler, because people are going to see it yet again as a composer exploiting a sensationalistic theme just to get his name out, or they’re just going to be downright offended by it, because he’s actually a murderous horrendous criminal.’ ”

He openly wondered how Führerbunker might be perceived. Events of WWII and Nazism are within the living memory of many people and the effects thereof are still felt everywhere. “This is not like writing an opera about the Napoléon regime, which happened over 200 years ago.” These are the same people responsible for trying to systematically exterminate Jews, Gypsies, Poles and Slavs. Not to mention Jehovah’s Witnesses, homosexuals, dissenting clergy, communists, and socialists.

“This project sounds seriously offensive… But people need to know we are treating it as a narration of the individuals involved, and not a glorification, not a cheesy dramatization, and at the same time, not a morality play. Hitler is being portrayed for what he was, an evil war criminal.”

When it came to the question of musical style, Ager was tempted to compose a mix of neo-Wagnerianism and expressionism. “No, that would be expected and rather cliché, he said. “In fact it could easily become campy.”

Ager also came up against a similar issue when working on his chamber opera Frankenstein, which he feared might come across as a one-dimensional parody. To combat this he casted Toronto-based Steven King, on his ability to portray the “abhorred monster” as an overgrown child, which more closely honoured Mary Shelley’s original story.

In light of scandalous operas, I couldn’t help but asking what Ager’s take on John Adam’s The Death of Klinghoffer, especially considering the recent controversy. He confessed he hadn’t seen it, but was aware of various arguments orbiting the Metropolitan Opera’s decision to cancel the planned HD cinema broadcast this summer over fears that it might fan global anti-Semitism.

The Met’s position was a mess. It acknowledged that they believed the opera was not anti-Semitic in itself, but due to pressure from the Anti-Defamation League, and (indirectly) the Klinghoffer daughters, they censored it anyway. What seemed so disturbing was the fact that many of these stances bypassed the actual substance of the work, which arguably expresses both sides of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. It doesn’t apologise for anything, and like all good political art, serves as a vessel for discourse.

In many ways political operas strive for something much more complex than simply a historical retelling or account of events. As Musicologist Robert Fink states, they attempt to, “counterpoise terror’s deadly glamour, the life-affirming virtues of the ordinary, of the decent man, of ‘small things’”.

Ager agrees it’s important to take the risk. The reverence involved with topics surrounding devastating suffrage is central, but as artists, it can sometimes cloud a distinct artistic statement with multiple layers of nuance. This weight can make it particularly difficult to work with. Like all artists, composers are not in the business of making everyone feel at ease. They create opportunities to confront atrocities that live on in our collective history – the good and bad, the beautiful and the ugly.

Controversy aside, and if history can be the ultimate judge, Ager confesses he is prepared to roll with any punches.

Führerbunker will premiere via The Centre for Opera Studies International (COSI) in the Spring, on February 11th at the Registry Theatre in Kitchener-Waterloo. A fuller production will also hit Toronto on May 1-2, 2015.

Michael Vincent

- THE SCOOP | Royal Conservatory’s Dr. Peter Simon Awarded The Order Of Ontario - January 2, 2024

- THE SCOOP | Order of Canada Appointees Announced, Including Big Names From The Arts - December 29, 2023

- Ludwig Van Is Being Acquired By ZoomerMedia - June 12, 2023