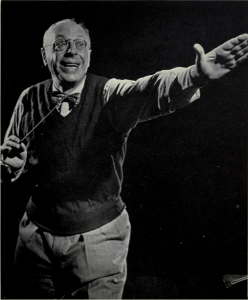

I first saw Lorin Maazel conduct at Plateau Hall in Montreal in 1962. He was touring with the French National Orchestra. He was 32-years-old at the time and a real whiz-kid. He conducted everything from memory and seemed to have the most precise stick technique I had ever seen. Among other works, he conducted Stravinsky’s Petrouchka and Berlioz’ Roman Carnival Overture. At the end of the Berlioz there is a loud sustained brass chord and Maazel dealt with it in the most theatrical way possible. He demonstratively dropped his arms while the brass players held their chord. Then, when it seemed they could not hold the chord a second longer, he flamboyantly cut them off. For much of his career, Maazel was that kind of conductor; he loved to draw attention to himself rather than to the music.

On that night in Montreal, he conducted a lot of flashy music and conducted it brilliantly. If you wanted brilliance, he was your man. If you wanted sensitivity or depth of feeling, well, better look elsewhere.

In the Footsteps George Szell

Years later, I had the opportunity to interview Maazel in Cleveland when he was the music director of the Cleveland Orchestra. As a successor to George Szell, he was a huge disappointment. In most of the standard repertoire, Szell had been authoritative. By contrast, Maazel seemed immature and erratic. In the interview, I found him pompous, with intellectual pretensions that were laughable. During my visit to Cleveland, he conducted the dullest performance of the Bruckner Fifth Symphony I had ever heard.

Maazel became known for performances in which the conductor pulled the music this way and that for no apparent reason. This was not interpretative insight; it was sheer wilfulness. A broadcast performance I heard Maazel conduct with the NY Philharmonic stands out in my memory. The music was the Beethoven Fifth. There were all manner of strange aberrations in the performance, but the one that got me was in the last movement. The main theme of the movement is that triumphal C major outburst after the long crescendo. Later comes the second main theme, played by the horns. For some reason, Maazel decided that there should be a fermata over the top note in the horn tune. Imagine Pavarotti holding the high B – there is no fermata in this score either – in “Nessun dorma.” I had never heard any conductor do this before, nor have I heard it since. Musically, it is indefensible. And in matters of taste it is simply beyond the pale.

Over the course of his long career – he began as a conducting prodigy at the age of 9 – Maazel was head of many major orchestras and musical organizations; these included the Cleveland Orchestra, the New York Philharmonic, the Bavarian Radio Symphony, the Munich Philharmonic and the Vienna State Opera. He conducted the prestigious Vienna Philharmonic New Year’s Concert on several occasions.

Birth of the Castleton Festival in Virginia

In his later years, Maazel mellowed a great deal and pontificated less as he became more at ease with himself. He married for a third time and bought a farm in Virginia. He had the idea that he would start a school-festival at the farm. This became the Castleton Festival; unfortunately, he probably started it too late in life and had only a few years to work on it. It was a worthy concept and showed that Maazel really cared about young people and about nurturing talent.

The last time I saw Maazel conduct was at the ill-fated Black Creek Summer Festival in Toronto in 2011. He brought the Castleton Festival Orchestra in for a few concerts. The one I heard was superb. Mendelssohn’s Incidental Music for a Midsummer Night’s Dream with readings from the play by Helen Mirren and Jeremy Irons. It was not repertoire I would have associated with Maazel, but he did it splendidly. His tempi were ideal, and stylistically it all made sense. Technically, Maazel was at the top of his game, seamlessly meshing the music and the readings.

Maazel the Master Technician

Maazel was renowned the world over as an orchestral technician. He knew how to rehearse; he had a great ear and an amazing memory. The performances he gave were nearly always well rehearsed, but one seldom left his performances feeling that the music had been well served.

In a video interview recorded just a few years ago and available on YouTube, Maazel comes across as exceedingly affable and self-deprecating; unfortunately, not many of the musicians who played for him remember him that way. He had a reputation for meanness that tended to offset the great respect musicians had for his technical skills.

Maazel made dozens of recordings, including complete cycles of symphonies by Beethoven, Brahms, Tchaikovsky, Mahler, Sibelius and all the rest. He also recorded Gershwin’s Porgy and Bess and Prokofiev’s Romeo and Juliet (complete) with the Cleveland Orchestra. His discography is indeed substantial, but I seriously doubt that we will be turning to many of these recordings as standard reference versions in the years to come.

Paul E. Robinson

Paul E. Robinson is the author of Herbert von Karajan: the Maestro as Superstar, and Sir Georg Solti: His Life and Music. For friends: The Art of the Conductor podcast, “Classical Airs.”

For more on Maazel by Paul, see “A Tale of Two Festivals: Castleton and BlackCreek.”

- SCRUTINY | TSO Lets Berlioz Do The Talking In Season Opener - September 21, 2018

- RECORD KEEPING | Even Yannick Nézet-Séguin Can’t Make Us Love Mozart’s La Clemenza di Tito - September 6, 2018

- RECORD KEEPING | Giovanna d’Arco With Anna Netrebko Explains Why The Best Operas Survive - August 30, 2018