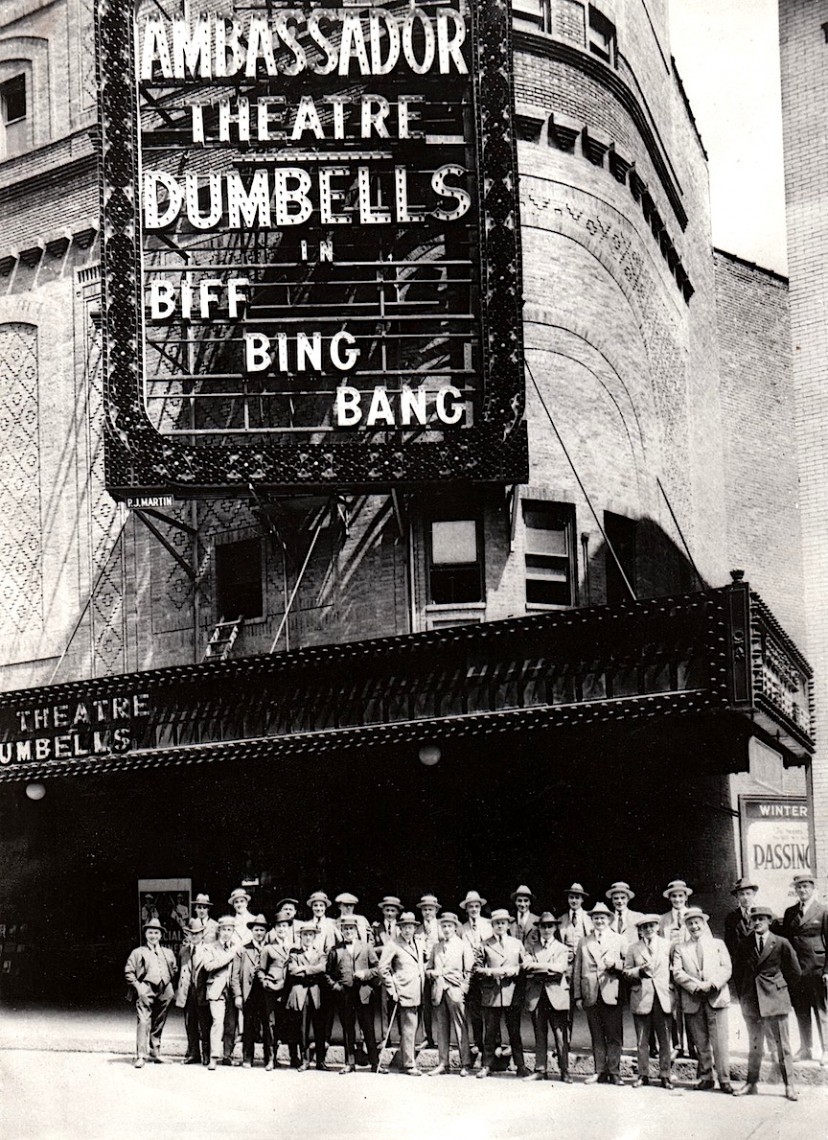

Toronto has a chance to experience a fascinating slice of Canadian history at Hugh’s Room on Saturday, when a group of local musicians, comedians and actors recreates the Vaudeville-inspired antics of World War I entertainer troupe the Dumbells, born in the muck and death-soaked trenches of Europe nearly a century ago.

- OPEN LETTER | Christina Petrowska Quilico Remembers Pierre Boulez - January 7, 2016

- Op-ed: The Compositional Voice and the Need to Please - September 4, 2014

- Onomatopoeia: The Thin Edge New Music Collective Sounds Off - May 10, 2014

The show follows the publication last fall of a history of the Dumbells and the “concert parties” that helped troops let off some steam in the midst of war.

Singer-songwriter Jason Wilson and Toronto storyteller Lorne Brown will help us relive what a concert party may have looked and sounded like, with the help of actors Jim Armstrong and Andrew Knowlton.

To help us appreciate what the Dumbells mean to Canadian history, Wilson has kindly provided an excerpt of his book, Soldiers of Song: The Dumbells and Other Canadian Concert Parties of the First World War, (Waterloo: Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 2012).

Welcome to a world far away and long ago — and yet strangely still very much a part of us:

In light of its lack of preparation and the questionable quality of its officers, the Canadian army was viewed, by some Canadians, as the “Comedian Contingent” at the outset of the First World War. By war’s end, however, the Canadian Corps—who were later dubbed the “shock troops”—would mature into one of the premier fighting formations on the Western Front. Still, concert parties of the Canadian Corps would ensure that at least some of that “comedian” quotient would be retained.

The seeds of black humour that inspired the likes of Monty Python, Saturday Night Live and SCTV were sown in the trenches of the Great War and Canadian concert parties were among the pioneers of this brand of comedy. To optimize the fighting potential of Canadian soldiers in the First World War, organized “concert parties” satisfied the official Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF; the administrative branch of the Canadian Corps) mandate of raising and maintaining the morale of Canadian soldiers. Ironically, concert-party performers were able to achieve this aim by mocking the military system and its high-ranking officers. Though many officers were aware of the subversive material in the concert-parties’ performances, they chose to ignore it because of its positive effect on troop morale; the soldier-entertainers were not merely following the impersonal objective of bolstering the morale of the army at large, in order for them to win the war but rather, more intimately, the performers sought to reach the individual soldier, in the interest of helping him survive the war.

The Canadian Corps’ concert parties helped soldiers enjoy a respite from the war while remaining literally and emotionally in the middle of it. The sonic assault of artillery bursts, alongside the prevalence of death and its unmistakable stench, always complemented the makeshift stages erected along the front lines; where troops watched one of their own channel a popular song from the music hall, act out a humorous and topical skit, or enjoy the most cherished component of the concert-party’s repertoire—the female impersonators. Over the course of the war, the comedic material of both Canadian and British concert parties transformed from the light fare offered in the British music hall to a darker humour that was “exclusive” to front-line soldiers. And while some topics (such as killing and dying) would remain largely taboo and were avoided by the concert parties, this exclusive brand of soldier humour, relevant primarily (and sometimes only) to the Canadian Forces, forged an enduring and vital bond between the soldier-entertainers and their audiences who survived the war.

Although they were not the first concert party formed at the Front, the Dumbells would become, over time, the Canadian concert party of the First World War. By war’s end, the Dumbells had adopted performers from several other Canadian Concert Parties, most notably the Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry’s (PPCLI) Comedy Company. As such, this study necessarily reviews all of the Canadian Corps’ concert parties more generally than concentrating exclusively on the Dumbells during the war. Leading up to the Armistice and in the years following the war, however, the study squarely spotlights that morphed entity that most Canadians living in this time period would come to know as the Dumbells.

Back in Canada, civilian audiences were introduced to the Dumbells and their satirical interpretation of the Great War through those soldiers who had seen the concert party perform in France. Among the pioneers of sketch comedy, the Dumbells are as important to the history of Canadian theatre as they are to the country’s social and cultural history. If nationhood was won on the crest of Vimy Ridge, it was the Dumbells who provided the country with its earliest soundtrack.

Two years after the First World War had begun, military officials in the CEF felt that troop morale was in need of repair. One remedy suggested was the organization of concert parties. As the war dragged on, professional entertainers had become prohibitively expensive for the Canadian military. The hope was that concert parties could entertain Canadian soldiers for free and, more importantly, raise the spirit of the soldiers, which had been in a tail spin due to the increasing horrors of the front lines. As early as 1916, various battalions within the Canadian Corps followed the example of their counterparts in the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) and formed their own entertainment groups. These concert parties comprised talented soldiers from within the battalions themselves who may have possessed a penchant for singing, performing, or acting.

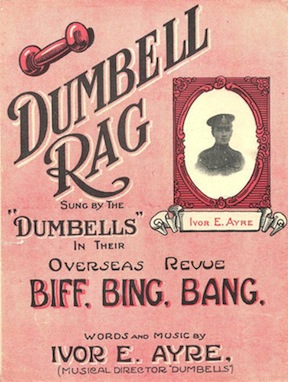

The musical and comedic content that made up most of the performances of the Canadian concert parties had their origins in the tradition of the British music hall. Borrowing from comedic themes and songs that were popular on the stages in London’s West End, Canadian soldier-entertainers appropriated British themes into a Canadian context. Whether it was in the adaptations of popular music-hall songs, or works they had created themselves, Canadian concert-party performers targeted many contentious issues that affected the Canadian soldier. By parodying real soldiers’ issues in their show—ranging from the inadequacies of the Ross Rifle to the popular subject of rum rations—the concert parties of the Canadian Corps were able to directly relate to the common soldier.

The musical and comedic content that made up most of the performances of the Canadian concert parties had their origins in the tradition of the British music hall. Borrowing from comedic themes and songs that were popular on the stages in London’s West End, Canadian soldier-entertainers appropriated British themes into a Canadian context. Whether it was in the adaptations of popular music-hall songs, or works they had created themselves, Canadian concert-party performers targeted many contentious issues that affected the Canadian soldier. By parodying real soldiers’ issues in their show—ranging from the inadequacies of the Ross Rifle to the popular subject of rum rations—the concert parties of the Canadian Corps were able to directly relate to the common soldier.

The surreal landscape of the war, the loss of life, and the misery of trench warfare had a profound effect on the content used by the singers and the comedians of the concert parties. And while there was a semblance of the innocence of the British music hall within the shows, soldier humour had, over the course of the war, become more coded and exclusive, and more faithfully reflected the atrocities of the Western Front and its unprecedented carnage. As far as the soldiers in the audience were concerned, their comrades on stage were telling it like it was.

That the entertainers were soldiers themselves further strengthened the bond between those both on and off the stage. Canadian soldiers embraced the concert parties with the knowledge that all of the entertainers had seen active duty. They were, in effect, seeing themselves on stage. Many entertainers returned to front-line service during the war, a fact that kept those who remained in the concert parties extremely aware of the war around them. Performers such as W.I. Cunningham and Norman “Nobby” Clarke of the PPCLI Comedy Company were taken out of the concert party and returned to active duty for the remainder of the war. Long before he was a Dumbell, Al Plunkett caught some shrapnel shortly after he and the rest of the 9th Brigade were being relieved at Sanctuary Wood in June 1916. Others, like Stanley Morrison and Leonard Young, also of the PPCLI CC, were seriously wounded, but continued as best they could. Cyril “Biddy” Biddulph left the Comedy Company and was killed at Monchy in August 1918. So, when a regular private from the Canadian Corps saw the one-legged Young or the previously gassed Red Newman or Gitz Rice perform, he saw performers with a commitment not only to entertaining the troops but also those who had, with their wounds, endured a rite of passage. These were soldiers who knew.

Dr Jason Wilson

For more information about Soldiers of Song: The Dumbells and Other Canadian Concert Parties of the First World War, click here.

For more information about Saturday’s show, click here.

And for more on Jason Wilson’s eclectic musical life, click here.

+++

Here’s something vaguely related from YouTube, an episode from It Ain’t Half Hot Mum, a 1970s BBC sitcom about a World War II concert party troupe:

JT

- OPEN LETTER | Christina Petrowska Quilico Remembers Pierre Boulez - January 7, 2016

- Op-ed: The Compositional Voice and the Need to Please - September 4, 2014

- Onomatopoeia: The Thin Edge New Music Collective Sounds Off - May 10, 2014