Last night, University of Toronto’s Faculty of Music hosted a concert in honour of John Weinzweig, whose 100th birthday would have been on March 11. There is an all-day symposium on his work and influence today. On birthday Monday, the Cecilia String Quartet presents a free, all-Weinzweig lunchtime concert at Walter Hall. But none of this matters.

- Classical Music 101: What Does A Conductor Do? - June 17, 2019

- Classical Music 101 | What Does Period Instrument Mean? - May 6, 2019

- CLASSICAL MUSIC 101 | What Does It Mean To Be In Tune? - April 23, 2019

There’s a maddening, stingingly practical truth to the world: No matter how good an idea, it is worthless until its time has come.

In the case of John Weinzweig, reality is just as brutal: His time had come while he was alive, and left with him when he died on Aug. 24, 2006.

His time as a serialism-influenced composer was up, as the art music world turned its attentions back to tonal writing. His time as a Canadian composer was up as the CBC shut its studio doors to a serious, consistent commitment to exploring the creators and creations of experimental art of any sort.

His time as a national culture builder was up, too, with the rise of national boundary-busting social media and all forms of streaming on the Internet.

The description of the John Weinzweig Centenary Project, which counts 22 highly respected and thoughtful Canadians on its advisory board, tellingly begins with this paragraph:

Known for his piercing wit, John Weinzweig once told the story of his recurring nightmare. In it, Canadians revered long-dead European composers with concerts, festivals and broadcasts dedicated to their music, ultimately leading to the demise of Canadian music. The John Weinzweig Centenary Project will ensure that his nightmare doesn’t come true.

With the greatest of respect, I’d like to point out that it has come true.

To be clear, I am not disparaging Weinzweig’s craft, nor the significant legacy he left inside the country. Also, the style in which he wrote may be passé, but Weinzweig wrote well.

Canadian music as a feather in a nationalistic cultural cap is also passé, but there will hopefully be a Canadian composer one day who will make a wider mark on the art music world much in the way as Howard Shore and Mychael Danna have left a deep international impression through their film scores.

The John Weinzweig Centenary Project continues:

Though there have been remarkable strides made, Canadian music still occupies a marginal position in the repertories of performers, ensembles, institutions and organizations across the country. During his lifetime, John Weinzweig devoted himself to this cause, and remarked on the anniversaries of Mozart, Beethoven and Bach – celebrated by ensembles all over the world – that he awaited the day when Canadian composers would be commemorated with similar veneration.

The Toronto Symphony Orchestra’s annual Mozart anniversary mini-festival comes around every year — as does the New Creations Festival, which wraps up tonight. Rather than focus exclusively on Canadian works, the New Creations Festival pairs homegrown music with pieces from other countries.

The explicit message is not a celebration of Canadianness for its own sake, but a celebration of music written and performed here being as good as what is being written and performed in New York, Los Angeles, London, Paris and St Petersburg.

Soundstreams has made a point of pairing Canadian works with international ones, as have New Music Concerts and Continuum Contemporary Music.

But I’m only partly addressing Weinzweig’s main plea, which is for a Canadian composer to receive equal veneration with the greats of the Western canon.

The obvious answer is to say that there isn’t a Canadian composer who has written music compelling enough to catch on in other parts of the world. But that’s too easy.

No, Weinzweig’s music is not easily accessible, and it really is out of fashion now. But Bach’s music was out of fashion for a long time, too, so we know that the taste of the day has a tenuous relationship with quality.

Instead, what we’re lacking is an international perspective. The Philip Glass’s and John Adams’s of the world have legions of apostles. Henri Dutilleux has advocates in Renée Fleming and conductor Stéphane Denève, who brings something to the orchestras he visits. The same is true for Oliver Knussen and Osvaldo Golijov, to name only a couple more.

There are dozens and dozens of classical Canadian singers, conductors and instrumentalists scattered about the world, but they rarely travel with a favourite Canadian composer’s score in hand.

How many Canadian scores have Sir Andrew Davis and Peter Oundjian introduced their other orchestras to?

Will the Cecilia String Quartet include any of Weinzweig’s string quartets in their touring repertoire? I guess we’ll have to wait and see. But we shouldn’t hold our breath.

How come even after 75 years of CBC and 55 years of Canada Council are the country’s own composers still marginal creatures?

I can’t help thinking of the parallels between Weinzweig and Benjamin Britten, both born in 1913. The first is a footnote, the second an emblematic figure of his times.

The young Britten had only modest success at home, doing very much the kind of work Weinzweig did — writing film scores and small commissions — until he went off to North America. He stopped in Quebec City and Montreal and Toronto, chatting up anyone and everyone, and leaving behind some music for people to play.

He and Peter Pears toured extensively throughout their working lives, with Britten not as composer but as accompanist, providing audiences with another point of contact. Britten conducted orchestras and made influential friends — his longstanding friendship with cellist Mstislav Rostropovich was invaluable to helping propagate the composer’s instrumental music.

Weinzweig expended a lot of time and energy teaching, helping found the Canadian League of Composers in 1951, presiding over the Composers’ Authors’ and Publishers’ Association of Canada, agitating for the foundation of the Canadian Music Centre. This was very important to nurturing a community of composers, but not a community of apostles and listeners.

If Weinzweig had devoted all these hours to international networking and touring, would his legacy have been any different?

In the new world order ruled by YouTube and streaming, let’s applaud our founding voices, but let’s also use them as reminders that it’s time to think differently, to look outward, not inward.

Rather than agitating for someone to apply emergency CPR to CBC Radio, we should be looking at ways to get someone in Johannesburg to hear the music of Brian Current and go, Wow, I must have me some of that. We need students at the Beijing Conservatory to come face to face with our brightest young lights and feel the music in their fingers and bows and larynxes.

There are people doing exactly that every day, but they’re doing it by scraping together temporary arrangements.

How much more could we accomplish if we had a well-funded Organization for the Export of Canadian Culture that recognized online efforts as well as touring and exchange programs?

There is one last, key point I want to raise: the role of the amateur in a composer’s enduring success.

I mentioned this in my third installment on Benjamin Britten last Sunday: One of his distinguishing features among 20th century composers was that he wrote music for amateurs.

Even if I never darkened the lobby of an opera house, I might have sung Noye’s Fludde as a child. I was playing Beethoven Bagatelles at age 8. But I wasn’t playing John Weinzweig.

If you get a child interested in your music, chances are that connection will last for the rest of their lives.

What are your thoughts?

+++

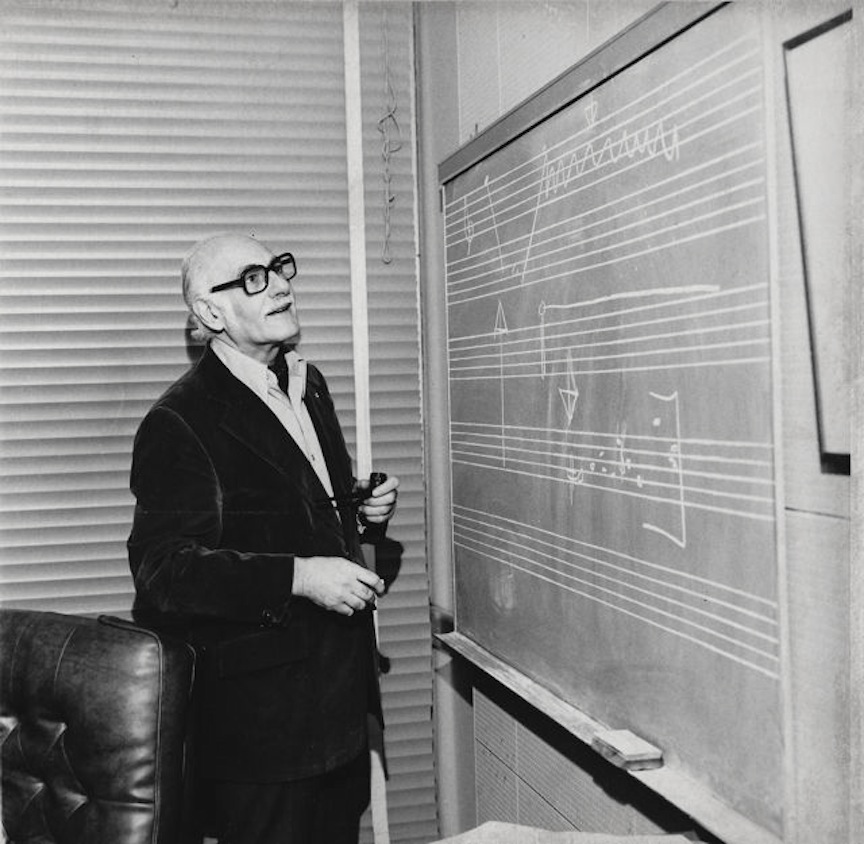

Here is Weinzweig at his most whimsical, in a Bravo! video from 1999 featuring himself and divas Measha Brueggergosman and Jessica Lloyd:

John Terauds

- Classical Music 101: What Does A Conductor Do? - June 17, 2019

- Classical Music 101 | What Does Period Instrument Mean? - May 6, 2019

- CLASSICAL MUSIC 101 | What Does It Mean To Be In Tune? - April 23, 2019