We think of Benjamin Britten as an opera composer, but he wrote for ballet as well, and the rhythmic vitality of much of his instrumental music continues to inspire choreographers.

- Classical Music 101: What Does A Conductor Do? - June 17, 2019

- Classical Music 101 | What Does Period Instrument Mean? - May 6, 2019

- CLASSICAL MUSIC 101 | What Does It Mean To Be In Tune? - April 23, 2019

According to the excellent background information on Benjamin Britten and his music published by the Britten-Pears Foundation, the would-be composer produced his first ballet score, Plymouth Town, at age 17.

It is described by the Foundation as, “A dockside morality tale slightly indebted to Stravinsky’s Petrouchka.”

Throughout his life, Britten was not shy about adapting music from other times and places. This is an hourable, centuries-old English tradition that would have earned scorn from a Mid-Century Modern North American or German composition professor.

Dance music is a great window into this eclecticism. I also think this is a fine way to begin appreciating why Britten’s creations resonate so well a century after his birth — at a time when the rest of culture is open to borrowing and adapting across cultures in musical mashups and kitchen fusions.

In 1938, Britten took some music he had appropriated for a film score from Gioachino Rossini and turned it into the ballet score Soirées musicales. It was so well received that he then wrote a companion, Matinées musicales. (Publisher Boosey & Hawkes says Balanchine turned both suites into a new ballet, but it doesn’t show up on the official George Balanchine Trust list.)

Here is conductor Desar Sulejmani at a concert in Düsseldorf two years ago, taking us through the first two-thirds of Matinées musicales:

At the experimental end of Britten’s aesthetic is his ballet score The Prince of the Pagodas, initially choregraphed by John Cranko.

In Part I of this series, we learned of Britten’s Canadian connections, made during the nearly four years he spent away from England before and during the outbreak of World War II.

Britten’s interest in the music of Bali was sparked by Canadian composer Colin McPhee, who had just returned from several years of learning and absorbing the musical traditions of gamelan.

Here are Britten and McPhee recorded in 1941 playing three Balinese pieces (Pemoengkah, Gambangan and Taboeh teloe) on two pianos:

Britten and partner Peter Pears went on an extended world recital tour for five months in 1955 and 1956. The couple took a two-week break in Bali, followed by nearly two weeks in Japan.

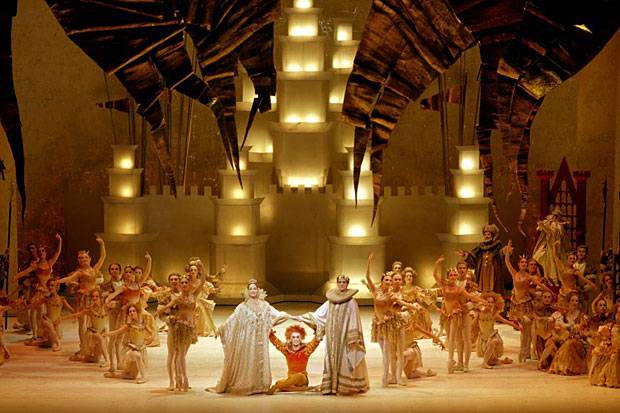

The result of this personal contact with Balinese music was The Prince of the Pagodas, premiered by the Royal Ballet in 1957.

This sensibility found its way into Britten’s other music during the second half of his working life.

Here are the opening scenes from Prince of the Pagodas from a 1990 revival of Kenneth MacMillan‘s 1989 production for the Royal Ballet (dancer Jonathan Cope is amazing the Prince, who enters in the third video clip), followed by an an extended audio clip of the enchanting “Bali Rice Terraces” beautifully performed by the London Sinfonietta under Oliver Knussen:

Britten’s most significant legacy comes from his operas. My favourite is Gloriana, an initially not-so-successful effort for the the celebrations around Queen Elizabeth II’s accession to the throne.

It contains a masque for Elizabeth I where the festive music is provided by the chorus as well as the orchestra. Britten assembled the six Choral Dances into a freestanding piece which MacMillan choreographed in 1977.

Here, for a bit more Toronto content, are some of the Choral Dances, as sung by the Hart House Chorus in 2002:

There is also quite a bit of music Britten wrote for concert purposes that continues to find its way onto sprung floors.

One prime example is Diversions, a piano concerto-like collection of theme and variations written for Paul Wittgenstein (the same left-handed pianist who commissioned Maurice Ravel’s now-famous concerto) in 1941.

The music practically screams for choreography, and Christopher Wheeldon obliged with Thirteen Diversions for American Ballet Theatre in 2011.

This is a fantastic recording of the music, I wish I knew by whom:

John Terauds

- Classical Music 101: What Does A Conductor Do? - June 17, 2019

- Classical Music 101 | What Does Period Instrument Mean? - May 6, 2019

- CLASSICAL MUSIC 101 | What Does It Mean To Be In Tune? - April 23, 2019