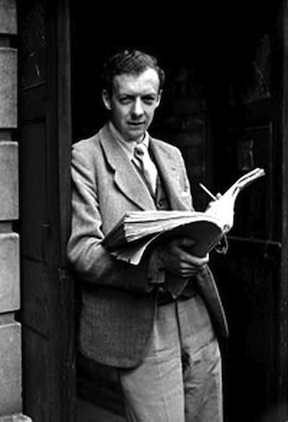

Of all the composer anniversaries this year, Benjamin Britten’s 100th is key. His music evokes so much with such an economy of means — and he speaks with a clear, modern voice.

Of all the composer anniversaries this year, Benjamin Britten’s 100th is key. His music evokes so much with such an economy of means — and he speaks with a clear, modern voice.

- Classical Music 101: What Does A Conductor Do? - June 17, 2019

- Classical Music 101 | What Does Period Instrument Mean? - May 6, 2019

- CLASSICAL MUSIC 101 | What Does It Mean To Be In Tune? - April 23, 2019

Britten, born 100 years ago on Nov. 22, was modern but comprehensible. He wrote for professionals as well as amateurs.

Above all, he understood music as a community act — a legacy that lives on in Aldeburgh, England, at the festival he and his life-long partner, tenor Peter Pears, founded 65 years ago.

It feels like there’s relatively little going on to commemorate Britten’s centenary among the bigger presenters in Toronto in 2013. But there is a lot to celebrate.

So I thought I’d try a multi-part Sunday series on Benjamin Britten leading up to the great Toronto commemoration of his legacy that Stephen Ralls and Bruce Ubukata have prepared as their final flourish as the Aldeburgh Connection — A Britten Festival of Song, which has its first concert on April 26.

Today’s first installment is about Britten’s early orchestral music.

But first, a bit of biographical background.

Out of curiosity, I cracked open my grandmother’s 1953 edition of Milton Cross’ Encyclopedia of the Great Composers and Their Music, published months before Britten turned 40. Despite his relatively young age, I found a chapter devoted to him.

Cross tells us how a 7-year-old Britten, growing up in Lowestoft, monopolised the family piano and would crawl into bed with symphony and opera scores. He had written a string quartet and an oratorio by age 9. “By the time he was sixteen he had produced a symphony, six quartets, ten piano sonatas, and many smaller works,” writes Cross.

Britten began to study with composer Frank Bridge in his teens. Bridge was keenly interested in the evolution of art music in Europe, and encouraged his student to be forward-thinking. Bridge, who bore the emotional scars of serving in World War I, was also a committed pacifist — something that rubbed off both Britten and Pears.

The composer’s early successes after leaving the Royal College of Music in London were the Fantasy Quartet for oboe and strings in 1934, a Suite for Violin and Piano in 1936 and the Symphonic Variations on a Theme of Frank Bridge, in 1938.

Aaron Copland reviewed the Variations for Modern Music magazine, writing, “The piece is what we would call a knock-out.”

With the poet W.H. Auden, Britten wrote some soundtracks for government film office documentaries. There’s a fascinating one (on many levels, from observing an early approach to “reality” filming, to this slice of British life) called Night Mail, from 1936 you can watch here. The last few minutes show off Britten’s ability to get maximum mood from minimal means.

In 1938, Britten, Pears and Auden left for the United States to get away from what looked like certain war on their side of the Atlantic.

A lot of music came out of this little voyage of exile, which lasted nearly four years, including Britten’s first opera, Paul Bunyan, and the Sinfonia da Requiem, which he wrote for Bridge, who had died in January, 1941.

You would think that the Toronto or Montreal Symphonies would have been keen to program the Canadian Carnival Overture, which Britten wrote in 1939. But it looks like people around here have forgotten about it.

Here is conductor Steuart Bedford (a longtime collaborator of Britten’s) with the English Chamber Orchestra, performing the Canadian Carnival Overture, which shows off Britten’s lighter side:

In 1938, Britten popped through Toronto to hear the CBC Radio Orchestra perform his Variations on a Theme of Frank Bridge, which had been commissioned by conductor Boyd Neel (who would later become dean of the Toronto Conservatory) for a Salzburg premiere in 1937. This is a 1967 recording by a group of conductorless musicians who called themselves the Camerata String Orchestra (and had ties to Neel):

And here is Britten’s Op. 4, Simple Symphony, a favourite of music schools everywhere. Its four movements have painfully cutesy names — “Boisterous Bourrée,” “Playful Pizzicato,” “Sentimental Saraband,” and “Frolicsome Finale” — but the writing is accomplished. Britten assembled the music from his childhood sketches and was 20 when he conducted the premiere at Stuart Hall in Norwich on March 6, 1934.

Here’s another nice older recording by a conductorless chamber orchestra, this one Italian, calling itself I Musici:

+++

If you have a favourite piece of Britten’s, please suggest it — and let me know why it’s a favourite. If you have anything else to share related to the anniversary, please do, and I’ll try to work it in to this series. You can email me at suchacritic (at) gmail.

John Terauds

- Classical Music 101: What Does A Conductor Do? - June 17, 2019

- Classical Music 101 | What Does Period Instrument Mean? - May 6, 2019

- CLASSICAL MUSIC 101 | What Does It Mean To Be In Tune? - April 23, 2019