“It’s a Stradivarius,” smiles David Hetherington as he unzips a long, narrow carrying case. Out comes a long, flexible, saw with a big crest on its shiny-toothed blade that says Stradivarius. The cellist is playing it to add a dash of eerie to Amici Chamber Ensemble’s first-ever afternoon at the movies.

- Classical Music 101: What Does A Conductor Do? - June 17, 2019

- Classical Music 101 | What Does Period Instrument Mean? - May 6, 2019

- CLASSICAL MUSIC 101 | What Does It Mean To Be In Tune? - April 23, 2019

Silent movies were typically accompanied by a pianist or an organist who would improvise the tempo and the mood necessary for each scene. It’s more rare for a live ensemble to be present in front of the flickering screen — and should be a treat for movie buffs, as well as anyone interested in checking out a classical chamber-music ensemble outside its popcorn-free natural element.

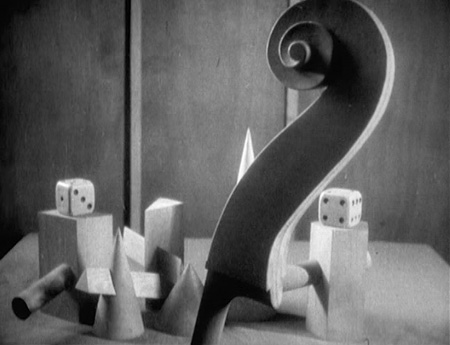

The TIFF Lightbox screening-slash-concert begins at 3 p.m. The films are: The Playhouse by Buster Keaton; Emak-Bakia by Man Ray; and The Heart of the World by contemporary Canadian art filmmaker Guy Maddin.

Amici pianist Serouj Kradjian took it upon himself not only to compile and arrange soundtracks for the Keaton and Maddin films — featuring pieces by Francis Poulenc, Darius Milhaud, Camille Saint-Saëns, Igor Stravinsky and even Johann Strauss, among others — he composed a brand-new piece to go with the 16-minute Emak-Bakia.

Amici’s core trio — Kradjian, Hetherington and Toronto Symphony Orchestra principal clarinet Joaquín Valdepeñas — were bandying about ideas for future concerts.

They were talking about a programme of pieces by composers who also wrote for film when Hetherington thought it would be interesting to present one silent film with two different soundtracks, “to show how the music affects how we see the film,” says the cellist.

But that turned out to be impractical. “Finding the right film isn’t so easy,” says Hetherington.

The trio then settled on an early Alfred Hitchcock movie, only to discover that getting approvals to change anything related to classic films can get complicated.

Fortunately, TIFF programmers came to the rescue with a list of excellent candidates already in the fesitval’s vaults, and which wouldn’t pose problems with rights or permissions.

All three works are being screened in from old-school 35mm prints. And the trio, along with guest violinist Yehonatan Beric, will play the original way, as well, following the flow of the video rather than relying on digital timers and prompts.

It’s meant a lot of practice and, for Kradjian, a lot of detailed work in nipping and tucking individual sections of music to make sure that the players stay in sync with the actors.

Kradjian figures he spent a month-and-a-half composing and arranging the soundtracks. That work, along with the rehearsals, have been done with the help of YouTube videos.

In a nod to the original silent film accompanists, Kradjian will improvise at the piano for a few minutes, but the rest of the music is as tightly scripted as the moving pictures.

The object of their rehearsals, Hetherington explains, is to get past the notes and give the music a natural, flexible feel — kind of like the singing saw that will be part of the instrument collection.

These musical pros wouldn’t want anyone to think this is their first time playing in a movie palace.

To find out a bit more about this adventure, click here.

Here is Emak-Bakia, with a soundtrack written and performed by Paul Mercer:

John Terauds

- Classical Music 101: What Does A Conductor Do? - June 17, 2019

- Classical Music 101 | What Does Period Instrument Mean? - May 6, 2019

- CLASSICAL MUSIC 101 | What Does It Mean To Be In Tune? - April 23, 2019