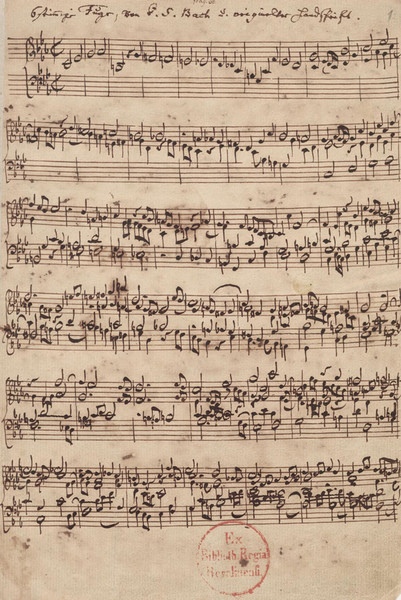

Long scholarly articles detail the musical and mathematical puzzles J.S. Bach (1685-1750) embedded in A Musical Offering (Musicalische Opfer, BWV 1079), a sequence of two fugues, 10 canons and a sonata based on a theme supplied by King Frederick the Great in 1747. It can be enjoyed in passive listening, or carefully dissected as it unfolds.

The jokes, asides and number games Bach embedded mathematically in this score have spawned countless debates on meaning. But we don’t have to go there in order to appreciate the craft of a composer at the peak of his already unnaturally fertile creative powers.

Torontonians have a rare chance to hear the full work live tonight at the Royal Conservatory’s Mazzoleni Hall, as part of the weekend’s Glenn Gould 80th anniversary festivities. David Louie will conclude the concert with the “Ricercar a 6” (six-part fugue), one of the most complex compositions for a solo instrument ever written in the West.

Despite the obvious appeal of the contrapuntal puzzles in A Musical Offering, Gould never recorded the work formally. Biographer Kevin Bazzana is pretty sure, however, that the pianist performed it with his chamber music collaborators at one of their many summer concerts in Stratford, Ont. in the 1950s.

Bach doesn’t provide instructions for the order in which the 13 sections are supposed to be played, nor what types of instruments are to be used in performance. The setup most widely used these days (and tonight) is: harpsichord (in solo and continuo roles), Baroque flute, two violins and a cello.

Because it is a big Gould weekend in Toronto, I thought I’d underline how shocking the Toronto pianist’s interpretations would have sounded to the ears of a typical mid-1950s music audience.

Crisply articulated Bach is the norm in 2012. But in 1952, except for the work of a handful of harpsichord players, the Bach most people heard was big and plush, weighed down by a focus on harmony (a vertical view of music) rather than the counterpoint (a horizontal view of music).

Gould’s hyper-articulated, horizontal approach was a sudden slap in the face — and we should never undervalue the power of surprise.

So here is A Musical Offering, presented in a musical Jenny Craig moment — before and after the historically informed musical revolution of a generation ago.

This is a 1958 recording of a version arranged and conducted by Karl Münschinger:

Here is how the piece is meant to sound according to period performance masters, the late Gustav Leonhardt (on solo harpsichord), Barthold Kuijken (Baroque flute), Sigiswald Kuijken and Marie Leonhardt, Wieland Kuijken (gamba) and Robert Kohnen (continuo harpsichord):

John Terauds

- Classical Music 101: What Does A Conductor Do? - June 17, 2019

- Classical Music 101 | What Does Period Instrument Mean? - May 6, 2019

- CLASSICAL MUSIC 101 | What Does It Mean To Be In Tune? - April 23, 2019