Everybody loves a good mystery — even more so if it taunts us with the challenge of being unsolvable. That, in a nutshell, is the secret behind the proliferation of books, scholarly articles and fan shrines focused on Glenn Gould.

Everybody loves a good mystery — even more so if it taunts us with the challenge of being unsolvable. That, in a nutshell, is the secret behind the proliferation of books, scholarly articles and fan shrines focused on Glenn Gould.

- Classical Music 101: What Does A Conductor Do? - June 17, 2019

- Classical Music 101 | What Does Period Instrument Mean? - May 6, 2019

- CLASSICAL MUSIC 101 | What Does It Mean To Be In Tune? - April 23, 2019

Gould is like fresh cheese in a mousetrap to anyone with even a passing interest in music, the spoken word, the nature of genius and the making of an icon.

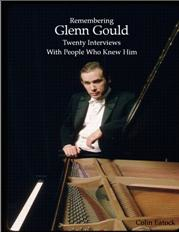

The latest entry in what can now legitimately be called Gould Studies, is Remembering Glenn Gould: Twenty Interviews With People Who Knew Him, by Toronto scholar, freelance writer and composer Colin Eatock. It is published by Penumbra Press in a tidy 190 paperback pages.

Divided into five chapters that each addresses a different aspect of Gould, the book works beautifully as either a quick overview of the man and artist or a refresher for those of us who have already spent years ensnared by the riddle of his life and artistry.

In other words, Eatock’s is the introductory survey course in our Gould Studies programme.

For anyone who has read a more comprehenisve biography, such as Kevin Bazzana’s wonderful 2003 book Wondrous Strange, Eatock offers up no surprises or revelations or insights — mainly because, like Stonehenge, every other curious individual has trod this ground and peered closely at each chip and crag in the stone before.

This takes nothing away from Eatock’s effort, which also tries to sweep away much of the unscholarly litter that less conscientious sleuths have cast upon Gould’s legacy over the past three decades.

In these interviews, we encounter Gould in all of his alluring contradictions. Through the people like his lawyer, assistant, sometime lover, childhood neighbour and collaborators at the CBC, we meet the introverted yet exceedingly chatty, serious yet humour-filled man. Through the eyes and ears of fellow musicians, we get points of view on the artist who was at once creator and interpreter.

Trying to separate author from story as much as possible, Eatock lays out each interview in question-and-answer form. He adds brief introductions and closing thoughts. Everything is neat and tidy, left in a make-up-your-own-mind format.

Whether or not he intends this, Eatock’s questions reveal that he came to Gould because he didn’t trust that Bazzana or Geoffrey Payzant (Glenn Gould, Music and Mind) or Otto Friedrich (Glenn Gould: A Life in Variations) or Andrew Kazdin (Glenn Gould at Work: Creative Lying) or Peter Ostwald (Glenn Gould: The Ecstasy and Tragedy of Genius) or Rhona Bergam (The Idea of Gould) or Mark Kingwell (Glenn Gould) or Katie Hafner (Romance on Three Legs) got the whole story.

Surely, if one could sit down one more time with all the people still alive who knew and worked with Gould, one could unlock the mystery of this singular character. But the enterprise is futile, condemned before it even starts to a rehash the same old stuff. Yet, just as Sherlock Holmes can’t resist wrestling with Moriarty one last time, Eatock jumps off the precipice — except that there is a ghost, not flesh and blood, in his arms.

I understand and sympathize with Eatock, because I have thought many times of doing exactly the same thing, of trying to reconcile the mound of eccentricities and lies and self-promotion with the unassailable individuality of Gould’s art that continues to move people of all ages and cultures. The survivors interviewed in the book are our last, tenuous, flesh-and-blood ties; when they are gone, all we will have left is what was set down for the record by people like Eatock.

Gould is the journalist’s dream subject, wide open with ideas and opinions and creative expression, yet possessing a hidden core that will forever be beyond our reach.

As Kingwell wrote in his book (more of a cultural and philosophical study of the Gould phenomenon than a biography, it’s the graduate seminar in our fictitious Gould Studies programme): “There is no unifying theme, no resolution to the tonic, in his life. His ideas about music govern that life, but those ideas themselves are contradictory, paradoxical, mischievous, and deliberately provocative.”

And so the mystery, and the music, will play on.

+++

If you’re in a conversational frame of mind, I suggest picking up Conversations With Glenn Gould, by Jonathan Cott (University of Chicago Press, 1984). It is, essentially, like being on the receiving end of one of the pianist’s multi-hour telephone monologues. The interlocutor, Cott, is just another curious journalist, asking the questions we keep dying to ask.

+++

I think Gould’s take on Beethoven’s Op. 35 15 Variations and Fugue is the perfect accompaniment here:

John Terauds

- Classical Music 101: What Does A Conductor Do? - June 17, 2019

- Classical Music 101 | What Does Period Instrument Mean? - May 6, 2019

- CLASSICAL MUSIC 101 | What Does It Mean To Be In Tune? - April 23, 2019