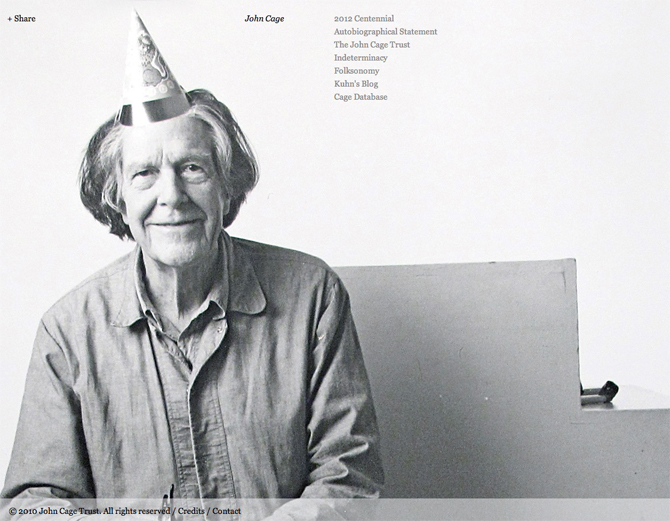

Today’s the day John Cage would have turned 100. Much has been written about the consummate innovator and his work over the years, as he yanked out the girders of the traditional Western musical edifice one by one, until he finally did away with even the semblance of visible form in his pursuit of the music of chance.

- Classical Music 101: What Does A Conductor Do? - June 17, 2019

- Classical Music 101 | What Does Period Instrument Mean? - May 6, 2019

- CLASSICAL MUSIC 101 | What Does It Mean To Be In Tune? - April 23, 2019

Early in his life, Cage left specific instructions about what to do in his music. So, even without the composer present, a pianist can, for example, prepare a piano exactly the way he wanted, and play a piece accordingly.

But during the 1940s Cage moved increasingly to music that was improvised as a series of chance encounters. With only specific time markings as guideposts, each performance was supposed to be vastly different, the product of tonight’s artists, each person’s state of mind, their connection with each other, and the corresponding state of the audience as a corporate entity as well as each individual viewer or listener.

In other words, the music of chance is a very complex dynamic, as complex as Thomas Tallis’ 40-part motet, except that the bulk of the result depends on being in the moment rather than following detailed instructions from a composer.

As long as I can lead 40 singers who can read music and stay in tune, we can perform Spem in alium. If we’re good at what we do, we might even be able to do it without rehearsal. If I have enough experience, I as the conductor know what the approximate speed should be, and how the dynamics might need to be adjusted (it’s interesting that composers of the day left no dynamic markings, choosing to ensure changes in volume by changing the texture of the music).

But to perform many of John Cage’s pieces, I and my fellow interpreters need to make sure our hands and arms and breath and senses are prepared, then start a piece in much the same way that a theatre-school student learns in her first group session to totally let go and fall backwards into the arms of the others without fear of hitting the ground.

This sort of complete reliance on others and trust in the potential of the moment strikes absolute terror not only in the typical classical musician, but in the typical audience as well. We are creatures of habit, of familiarity, of defined expectations.

Even people familiar and comfortable with listening to new music carry around a need for structure, which makes it awfully tempting to listen to a recording of a piece by John Cage in order to shape today’s performance. So much of art music is about interpretation rather than actual creation that it’s difficult to make that trusting fall backwards.

It’s been 60 years since Cage’s 4′ 33″ was first, um, performed. Nowadays, everyone knows that it’s about not making music but becoming aware of the space in which the gathering called a concert is taking place. But our awareness of what it is has changed the piece irretrievably: In a concert hall designed as a cocoon of silence, such as Koerner Hall for example, audience members will typically forget to breathe as they concentrate on silence rather than on the collective breathing, sniffing, candy-unwrapping, foot-shuffling and swallowing that is the (ideally) unheard backdrop of a Mahler symphony.

The lesson? We can never actually hear 4′ 33″ by following the classical music mantra of “this is what the composer wanted.” And that should be a source of liberation and inspiration for any musician in any genre, and a source of opening the mind of anyone in the audience.

But, 100 years after Cage’s birth and 20 years after his death, the struggle between creation and recreation continues in concert halls and recording studios around the world.

There’s a wonderful interview from 1981 that features John Cage in conversation with Merce Cunningham (the great experimental dancer and choreographer, who died three years ago). The two collaborated frequently, adding dance into this chancy performance art.

Cage clearly describes the place from which the two collaborators need to start: “We’re not starting from an idea or the expression of a feeling, but from being together in a particular space at a particular time.”

All those self-help books about being present, about engaging with each other and the world, come directly out of this attitude. This is what yoga workshops and meditation retreats are all about. It seems so clear and easy and simple, yet is remarkably difficult to actually do.

+++

Towards the end of this particular conversation, Cage comments on the practical usefulness of having seemingly unrelated things going on at the same time on a stage in a world increasingly filled with noise and distractions (this being said 31 years ago, before the birth of the Internet and the wide propagation of cell phones):

“It’s … useful in this society to be able to place attention not just one way but in two ways at least … so that we move towards a complex use of our faculties that will suit us in our everyday lives.”

Clearly, this is still a work in progress.

+++

Here’s the whole conversation:

John Terauds

- Classical Music 101: What Does A Conductor Do? - June 17, 2019

- Classical Music 101 | What Does Period Instrument Mean? - May 6, 2019

- CLASSICAL MUSIC 101 | What Does It Mean To Be In Tune? - April 23, 2019